Tapera No More: Indonesia Finally Stops Making Workers Buy Someone Else’s House

Tapera promised affordable housing. Instead, workers paid without benefits. MK strikes it down. What happened? What’s next?

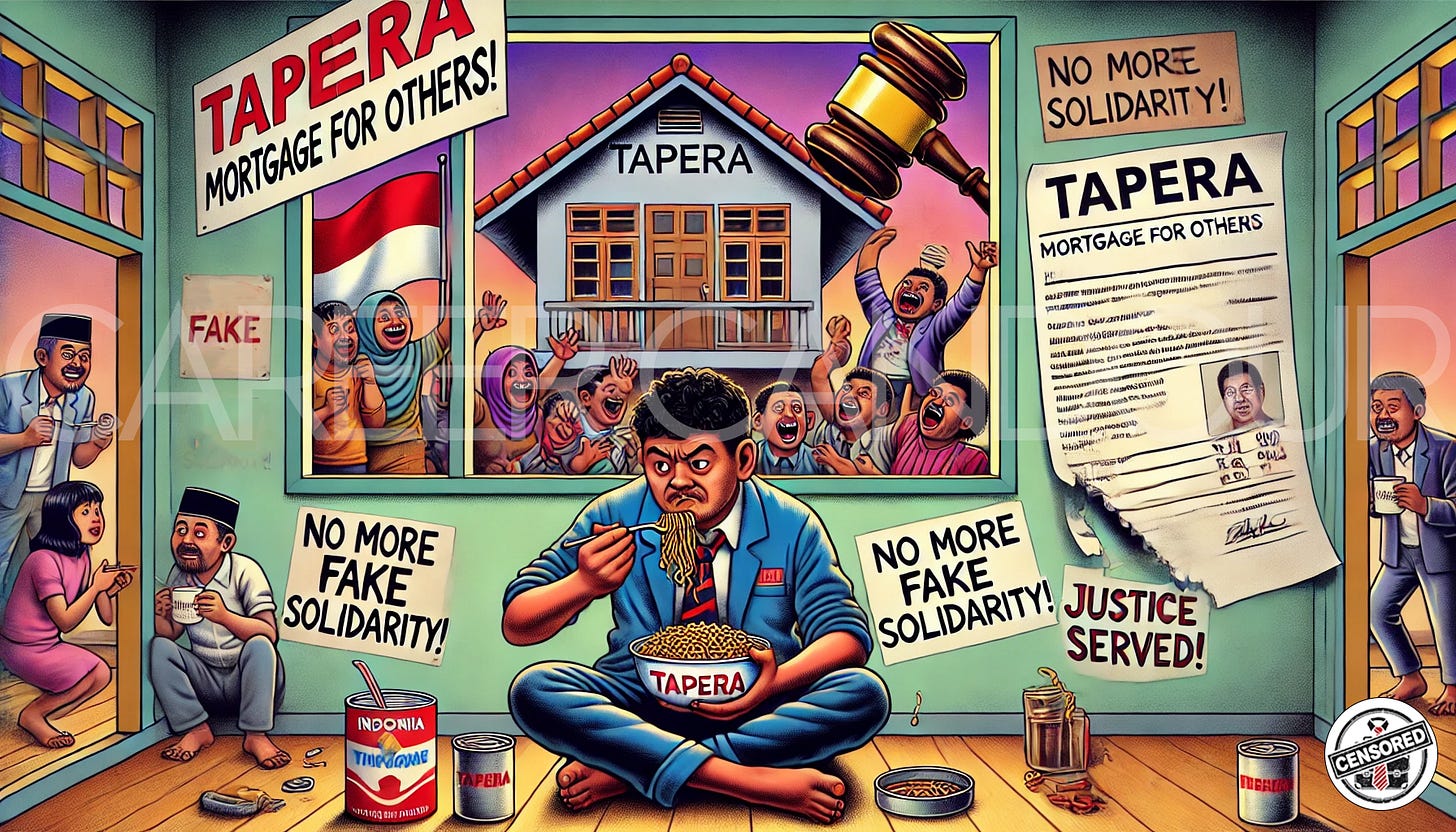

You work. You sweat. You tolerate five back-to-back Zoom meetings and a boss who still doesn’t know how to unmute. You inch through Kemang traffic with a thousand other souls dreaming of someday affording a mortgage. And just when you think you’ve earned a sliver more in your paycheck, a quiet deduction slides in: 2.5%. Not for your dream home, but for someone else’s. Someone lucky enough to qualify for a state-subsidized house, who just might now be relaxing in a tidy little rumah subsidi, while you return to your shared kos and reheat nasi goreng for dinner.

This was the brilliance of Tapera, the People’s Housing Savings Program that seemed suspiciously designed to make sure everyone but you got a house. It was mandatory. It was noble. And it was completely tone-deaf. Critics dubbed it Tabungan Perumahan Rakyat… kecuali kamu because yes, you paid, but no, you weren’t getting anything back anytime soon.

Now, thanks to the Constitutional Court, the tap’s been shut off. The mandatory part of Tapera is officially unconstitutional, and the nation collectively blinked in disbelief. Was that logic from the legal system?

Tapera: When Bureaucracy Dreamed of Building You a House

On paper, Tapera was a fairytale. The government, brimming with optimism in 2016, declared that it had found the silver bullet for Indonesia’s housing backlog. The Tapera Law promised to mobilize the collective financial strength of the nation’s workforce, pool it neatly, and transform it into mortgages for families who desperately needed a home. It was dressed up in the vocabulary of solidarity, but if you looked closer, it was solidarity by mandate.

The mechanics were simple enough: 3 percent of your salary would vanish every month. If you were classified as MBR (low-income) and had no home, you could apply for a fixed 5 percent mortgage. Everyone else, including those with homes, those living rent-free with family, or those saving for entirely different goals, were left with the joy of contributing to a pot they’d likely never benefit from.

By 2024, the cracks were visible. Middle-class workers, too “rich” for subsidies but too stretched for luxury, realized they were subsidizing homes for others while being locked out themselves. Young workers renting rooms questioned why they should fund mortgages when their biggest daily struggle was avoiding a bathroom queue. The government’s reply was that the program needed “better socialization,” as if the public’s outrage stemmed from misunderstanding rather than the obvious: they were being forced into a scheme that served them little to no direct purpose.

The problem wasn’t clarity. People understood exactly what Tapera was. They just didn’t like it. And that, in the end, was the program’s fatal flaw.

BPJS TK Already Does This Better

At some point in 2024, a glorious lightbulb moment happened in offices, on factory floors, in warung conversations: “Wait a minute… doesn’t BPJS Ketenagakerjaan already offer housing support?”

It wasn’t a trick question. The answer, annoyingly for Tapera’s architects, was a resounding yes.

BPJS-TK, through its Manfaat Layanan Tambahan (MLT) program, already does what Tapera claimed to be revolutionary for; helping workers get access to housing. It offers down-payment assistance, home renovation loans, and even mortgages, with fewer eligibility hoops to jump through. And while its interest rates have hovered a bit higher (recently around 8.5%) they’re still decent, especially considering the bureaucratic nightmare that is applying for anything subsidized in Indonesia.

More importantly, people already contribute to BPJS-TK. It’s on the payslip. It exists. It’s functional. It has a website that mostly works. So when Tapera waltzed in and asked for another 3% slice of your hard-earned salary, the public response was essentially, “Mas, kita udah bayar, loh.”

Tapera duplicated the service, added complexity, increased the payroll burden, and offered less access in return. It told workers, “You don’t qualify for the house, but you do qualify to fund someone else’s.”

That’s when people started feeling like they were being double-charged for one mediocre service while a parade of ministers declared the problem solved.

BPJS-TK, for all its flaws, at least didn’t pretend. Tapera came out swinging with shiny infographics and a heavy hand… and forgot the part where the public gets something meaningful in return.

Why Am I Paying for Someone Else’s House While I Rent a Kos-Kosan?

Tapera’s fatal flaw wasn’t that it tried to solve a problem. It was that it solved the wrong one, using the wrong people’s money. The policy somehow managed to make homeownership feel even further away for the very people it claimed to help.

Imagine you’re 28, renting a cramped kos in a building that predates smartphones. Your income is modest, but you’re not poor enough to qualify as MBR. You don’t own a house, don’t want a house yet, and frankly, you’re just trying to afford a better mattress. Suddenly, you’re informed that 2.5 percent of your salary is going to Tapera. Not voluntarily. Not as an investment. But as a legal obligation.

You don’t qualify for the 5 percent subsidized mortgage. You can’t access any immediate benefit. All you get is a digital account that tells you your money is being invested somewhere, maybe in bonds, maybe in other people’s front doors.

This isn’t social safety. This isn’t targeted subsidy. This is a savings tax wearing the cheap disguise of a housing program.

And what about freelancers, gig workers, and the self-employed? The plan was to include them too. A GoFood driver making daily ends meet would also have been compelled to chip in. Into a fund he’d likely never touch. The word keadilan was tossed around in speeches, as if the dictionary had quietly updated its definition to include “mandatory payroll deduction regardless of context.”

The people noticed. And they didn’t buy it. Solidarity is beautiful when it’s chosen. Tapera tried to legislate it into existence and call it virtue. In practice, it felt more like being pickpocketed and then applauded for your generosity.

Enter Mahkamah Konstitusi: The Unexpected Hero in the Housing Sitcom

Tthe Constitutional Court’s 2025 decision on Tapera delivered a moment of collective catharsis.

Case No. 96/PUU-XXII/2024 was brought forward by unions and advocates who had grown tired of being told that “mandatory” meant “helpful.” And in a rare act of institutional awareness, the Court actually listened. It acknowledged the thing most policy architects refused to say out loud: you can’t force everyone to pay into a housing scheme they’ll likely never benefit from and still call it justice.

In its ruling, MK struck at the heart of the issue. It didn’t just nitpick technicalities. It called out the coercion, the overlap with BPJS-TK, the disproportionate burden on workers, and the spectacular vagueness of what people were actually contributing toward. It allowed Tapera to continue existing, but declared its mandatory participation clause unconstitutional.

The government was given two years to redesign the system. Meanwhile, payroll officers across the country let out the deepest sigh known to bureaucracy. Unions called it a win for workers’ rights. Employers clinked glasses at HR seminars. Middle-class employees quietly celebrated not having to donate monthly to an invisible, unaffordable dream.

All it took was one Court ruling to do what three years of state socialization campaigns could not: get people to stop resenting a housing policy.

Tapera’s legal takedown was about public sanity. It reminded everyone that somewhere in the machinery of the state, there are still levers that work.

Indonesia does need a housing solution. That part isn’t controversial. The backlog is real. Millions still struggle to access livable, affordable homes. The question has never been whether the government should act, but how. And for whom.

What Tapera offered was a policy built on the idea that if you forcibly save workers’ money, something vaguely positive would eventually happen. Maybe. It assumed that if the state designed the funnel, the water would somehow find its way into the right glass. Instead, most people just watched their salaries shrink and their access stay exactly the same.

The Constitutional Court’s decision dismantled a set of faulty premises dressed up as policy. That everyone should be treated as a potential mortgage customer. That being forced to save is the same as being empowered.

The next phase should be honest: targeted support, voluntary options with real benefits, and a system that doesn’t punish people for not needing a mortgage today. Until then, let Tapera’s fall be a reminder that fairness can’t be reverse-engineered from payroll deductions.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we guide companies in Indonesia through compensation structuring, compliance, and workforce policy. Contact us to stress-test your employment policies before they hit the wall.