Why Selling Yourself Feels So Awkward (and What to Do About It)

Struggling to sell yourself in interviews? You’re not alone. Learn why self-promotion feels so hard, and how to do it without sounding arrogant.

There comes a moment, somewhere between adult taxes and back pain, when you must condense years of expertise, pattern recognition, and quiet brilliance into a 45-minute Zoom call. It’s called a job interview. Sometimes it’s disguised as a “coffee chat,” which is corporate code for “we will judge you but pretend not to.”

The task? Sell yourself.

The problem? You’ve never thought of yourself as a product.

You don’t have a brand deck. Your “unique value proposition” is mostly just being excellent at things that feel, well, obvious.

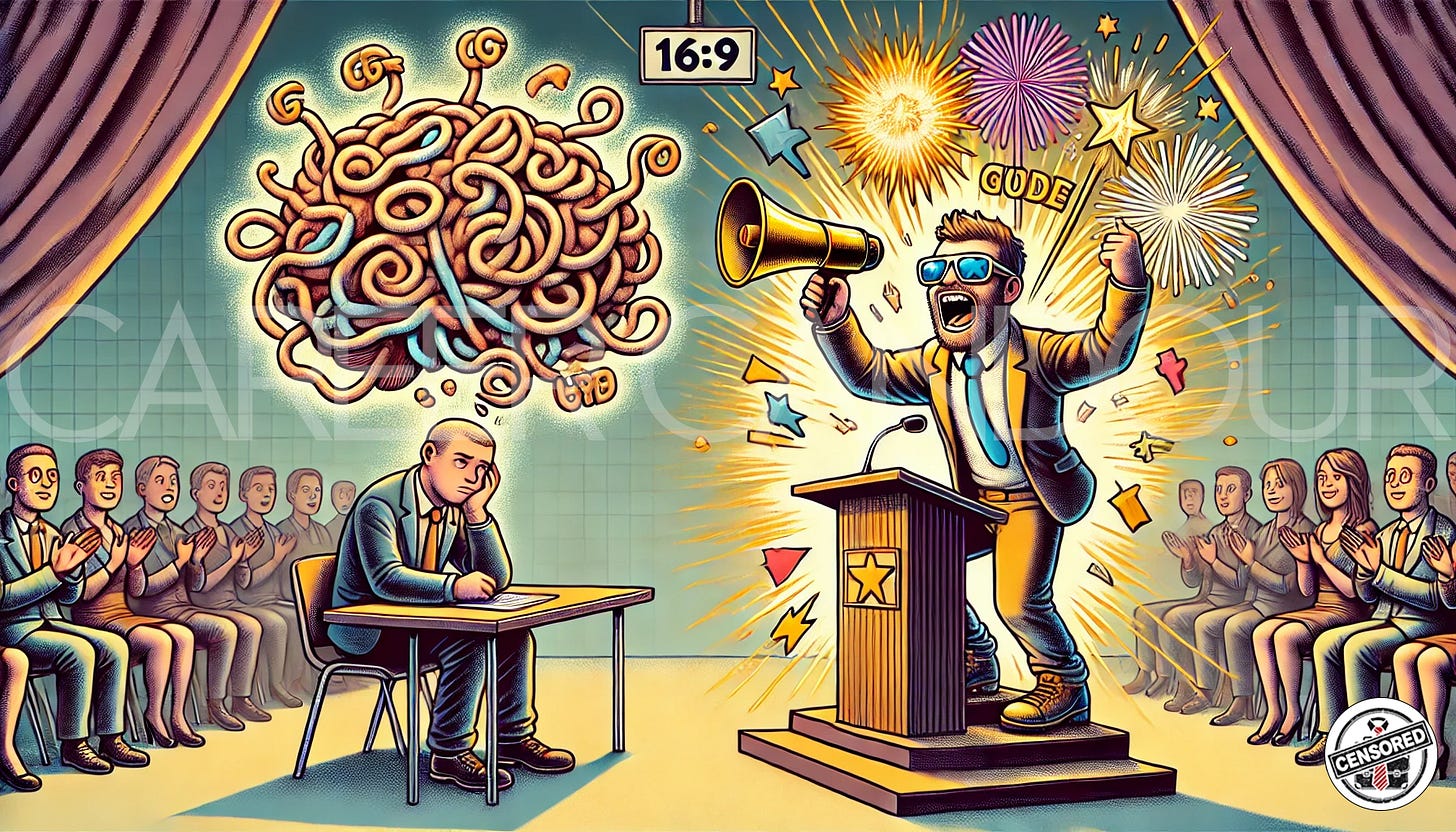

And that’s the mind trap. If something is easy for you, it must be easy for everyone. It’s not. But trying to explain that without sounding like you have a LinkedIn bio written by a minor cult leader is a dangerous game. Swing too soft, you disappear. Swing too hard, you become a walking TEDx Talk.

So we avoid the swing. We hope our excellence speaks for itself, even though it’s clearly mute. The result? Brilliant people go undersold, over-edited, and mispriced.

When You’re Good at Something, You Should Definitely Pretend You’re Not

The better you are at something, the less likely you are to think it’s worth mentioning. Competence, when well-developed, starts to feel suspiciously like breathing. You forget you had to learn how to do it in the first place. And if it didn’t involve sweat, agony, or a tragic backstory, your brain files it under “not worth talking about.”

This is not humility. This is bad data.

Psychologists call it the effort heuristic; our charming tendency to equate value with struggle. If something feels effortless, we assume it must be worthless, at least to others. This leads to the incredible logic of “if I didn’t suffer, it doesn’t count.”

So when someone asks you to walk through your accomplishments, you experience a kind of internal amnesia. “Accomplishments? What accomplishments? I just did the thing.” You assume everyone else can do it too.

They cannot.

Meanwhile, Mark from Sales is turning light admin into mythology. He had one meeting, cc’d legal, and walked out describing the experience as a “cross-functional orchestration of enterprise-level alignment.” And Mark is getting promoted.

Your internal signal for “valuable” is broken. Because effort isn’t what buyers (or interviewers) are paying for. They’re paying for results, certainty, and risk transfer. Ironically, the easier something feels for you, the more valuable it often is. You’re doing in 45 minutes what would take someone else six weeks.

“Easy for Me” Syndrome: The Silent Killer of Self-Worth

It begins with the curse of knowledge, which sounds like something out of a fantasy novel but is disappointingly real. Once you’ve acquired a skill, your brain conveniently deletes the memory of what it was like not to have it. You no longer recall the learning curve, the pain, the confusion. It now feels obvious, and obvious things feel cheap.

Then the false consensus effect joins in. That’s when you start assuming that everyone else shares your strengths, because they seem so… basic. You’re not bragging. You’re not minimizing. You’re just so used to your own mental architecture that it doesn’t look special anymore.

This leads to a bleak but common scenario: your most valuable, defensible skills, the ones others would gladly pay for, become functionally invisible to you. Because they’re too familiar to feel impressive. You look at them and think, “Well, this is just common sense.”

It isn’t.

When you finally gather the courage to say, “Actually, I’m really good at this,” you risk sounding like a megalomaniac who just compared themselves to Steve Jobs. The line between calm confidence and bizarre self-worship is paper-thin. Especially in an interview. Especially if your interviewer has never seen someone do what you do.

The result? Silence. Or vague language. Or another lost opportunity to own your edge, just in case someone might misunderstand you as someone who actually knows their worth.

Between Underselling and Arrogance Lies the Valley of Death

After years of brushing off your contributions as “just part of the job,” you’ve accepted that what you do might actually matter. You are now emotionally prepared to articulate your impact.

Until you try.

The words come out of your mouth and immediately betray you.

“I reduced enterprise sales cycles by 40% with a new legal triage system,” you say confidently. Then you immediately feel like you just compared yourself to Einstein. Suddenly, you’re sweating. You panic. You backpedal.

“It was really a team effort,” you mutter.

“I just happened to be in the right place at the right time,” you offer, as if the universe accidentally dropped a fully executed strategy into your lap.

This is impostor syndrome. It thrives on ambiguity and context collapse, convincing you that confidence is arrogance and that clarity is self-congratulation.

But what if you go the other way? Speak boldly. Own the outcome. Deliver your line with the same conviction Mark from Sales uses to explain his fantasy football strategy. Then you risk sounding unhinged.

“I created a revolutionary framework.”

“No one’s done this before.”

“I just see things differently.”

Which translates to:

“I will start a coup by Q3.”

“I cannot collaborate.”

“I am about to suggest Agile… again.”

You are not just describing yourself. You are also trying to decode the biases, insecurities, and attention span of your interviewer. You’re guessing how much detail is too much. You’re guessing whether they’re even listening. You’re also guessing whether they’re intimidated, bored, or pretending to take notes.

The Interview: Theater of the Calibrated Humblebrag

The modern job interview is a 45-minute performance piece where you are expected to strike the perfect balance between being clearly exceptional and not making anyone feel weird about it. You are not here to show off. You are here to show just enough.

This is a performance of honesty, governed by unspoken laws and social guesswork.

Sell yourself, but softly.

Be confident, but not cocky.

Be humble, but not invisible.

Be personable, but not weird.

Above all, get hired.

To navigate this, you need something more advanced than vague advice about “being yourself.” You need tactics. This is where STAR gets some needed reinforcements with the C³O overlay:

Claim,

Conditions,

Confidence,

Observables.

Instead of saying you improved something, you give your interviewer a tiny, evidence-backed case study that speaks for itself. You say things like: “Under these deal sizes, with these constraints, I’ve got 80 percent confidence we’ll hit this outcome. Here’s what that looks like on day 10.”

This is how you communicate mastery without having to declare it outright. No grandiosity. No false humility. Just receipts.

You can also borrow from the credibility playbook: mention what would have gone wrong without your input, name failure patterns others fall into, and point to one small artifact that shows how the work actually happened.

And for the love of believability, talk in ranges. Speak like someone who lives in a world of variability, not marketing slogans. Say, “That test lifted conversions by 12 to 18 percent,” not “It crushed.”

Selling yourself is hard. Not because you’re not capable, but because you’re too close to your own work to see it clearly. You are describing a lived experience through the foggy lens of cognitive bias, all while your audience operates on a different wavelength, with different incentives and a limited attention span. And just to spice things up, you’re probably trying not to sound like a narcissist.

But this just means you need to be deliberate. The key is calibration. You’re aiming for precision. Being able to map your value to outcomes in a way that’s concrete, verifiable, and not insufferable is a skill… and one that interviews are actually designed to reward.

So when someone hits you with the inevitable “tell me about yourself,” don’t recite your resume or start listing adjectives. Instead, bring receipts. Anchor your claim to conditions. Express confidence in a range. Tell them what would have gone wrong if you weren’t there.

That’s not arrogance. That’s clarity. And clarity sells.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we work with thoughtful professionals to craft honest, evidence-backed self-pitches that resonate. Contact us to turn intuition into structured proof that gets results.