How Did Indonesia's G20 Economy Make Cambodia Look Like a Good Career Move?

Indonesia grows at 5% yet thousands flee to scam jobs in Cambodia, exposing weak wages, limited mobility, and a fragile job market beyond Jakarta.

Indonesia is a G20 economy.

Indonesia grows at five to six percent a year.

Indonesia has a vision. A Golden vision. Indonesia Emas 2045. Eight percent growth.

Superpower ambition.

And then reality taps the microphone.

Two thousand Indonesians flee a scam centre in Cambodia.

Not Australia. Not Japan. Not Germany.

Cambodia.

The Cambodia we are usually told is poorer, weaker, less developed, and faintly embarrassing to compare with Indonesia unless the comparison involves cheap garments or governance rankings.

Yet here we are.

For any educated observer, Indonesian or otherwise, this collision is hard to ignore. On one side sits the official narrative. A rising middle power. Post pandemic resilience. A nation on the cusp of something bigger, better, and finally deserving of its own hype. On the other side sits a queue of Indonesians at an embassy gate, asking for help after escaping illegal, coercive, and dangerous work in a poorer neighbour because, at least initially, it looked like an upgrade.

This is not a story about Cambodia. It is not even primarily a story about scams.

It is a story about margins. About opportunity as it is actually experienced, not presented. At some point, a serious question becomes unavoidable.

What is the real state of Indonesia’s job market?

Not Jakarta. Not the macro slide. Not the ministerial talking points. Indonesia, in full. Nooks, crannies, and kabupaten included.

When Cambodia starts to look like a rational gamble, something fundamental is not adding up.

The Statistical Middle Class

Indonesia officially defines “middle class” as anyone spending roughly Rp 2 million per person per month. That is about three and a half times the poverty line. By this measure, millions of Indonesians have arrived. They are no longer poor. They are middle class.

It supports narratives of resilience and progress.

It helps explain why the economy keeps moving,

It helps explain why consumption does not collapse,

It helps explain why the malls stay busy.

In lived terms, it is far messier.

At this level, middle class life is precarious.

One motorbike repair can wipe out a month’s margin.

One illness can force a family to borrow.

One contract that is not renewed can undo years of slow, careful progress.

There is no buffer, only balance. Most people in this category sit at the very bottom of the bracket, not planning for the future but managing the present.

They are not investing. They are not accumulating assets or options. They are standing upright, economically speaking, and hoping the ground does not shift.

People do not experience life as a multiple of the poverty line. They experience it as the quiet stress of bills that just about get paid. As the feeling that effort does not lead to advancement, only to maintenance.

This is why:

An S1 graduate selling bakso in Kupang does not feel middle class, no matter what the data says.

A driver from Banyuwangi moves from town to town chasing work instead of building a base.

Jakarta’s job market feels crowded, and unforgiving even for those who are technically doing fine.

If this is the middle… what does the bottom actually look like?

Jakarta Is Hard. The Provinces Are Harder

Jakarta, for all its congestion, and pollution, remains Indonesia’s pressure valve. It is where jobs exist, where networks cluster, where information moves faster. If there is opportunity anywhere, it is there, or at least the impression of it. People come because everywhere else is harder.

Step outside Jakarta and a small number of major hubs, and the labour market changes character. In many provinces, employment is more about occupation. Something to do. Something that fills the day.

Work often means:

Smallholder agriculture, where margins shrink each year and productivity barely moves.

Informal trade that never scales beyond survival.

Casual construction, paid by the day, dependent on weather and connections.

Family warungs that exist to ensure someone in the household is technically working.

And then there is waiting.

Waiting for CPNS, treated not as one option among many, but as the last credible promise of stability. Waiting for a miracle. Waiting for a cousin to call from Batam, or Bekasi, or anywhere that sounds like it might have jobs.

Official unemployment numbers stay low because unemployment is a luxury. People cannot afford to be idle. They do something, anything, to stay afloat. But productivity is low, wages are flat, and the idea of upward mobility feels distant, almost theoretical.

There is work, yes. The country is not idle.

There is progression, no. Not in a meaningful sense.

Earning two to three million rupiah a month in this environment becomes both survival and ceiling. It is enough to endure, not enough to advance. Once that is understood, the Cambodia story stops feeling absurd, and begins to feel like a rational response to a labour market that offers effort without trajectory.

Cambodia Is Not Better, but the Offer Was

No serious observer is claiming that Cambodia is a stronger or more advanced economy than Indonesia. Cambodians themselves migrate abroad in large numbers, often under difficult conditions, in search of better work.

But this is about relative opportunity at the margin, and what a single job offer looks like when placed against a very limited set of domestic options.

For a young Indonesian, the local menu is often bleak.

One to two million rupiah from farming or irregular labour, dependent on seasons and family land.

Three to four million from informal urban work, eaten quickly by rent and transport.

No clear entry into formal employment.

No credible timeline that suggests next year will be meaningfully better than this one.

Against that backdrop, an offer of eight hundred to fifteen hundred US dollars a month is attractive.

Free housing.

Free food.

Office work.

Air conditioning.

A job title that sounds modern enough to explain to parents.

The mechanics matter too. There are no language exams. No years of training. No agency fees like Japan. No lottery systems like Australia. Often just a passport and a plane ticket, sometimes even fronted by the recruiter. Compared to legal migration pathways, it looks fast, simple, and achievable.

Yes, many did not know it was a scam. Yes, many were trafficked, coerced, or trapped once they arrived. That part is undeniable.

But the initial decision to leave Indonesia for Cambodia was not irrational. It was a calculated gamble in response to a domestic labour market that offered effort without reward.

When an illegal, dangerous sector in a poorer country can outbid the legitimate economy at home, the problem lies in the gap between what Indonesian labour is worth and what Indonesian workers are told they should accept.

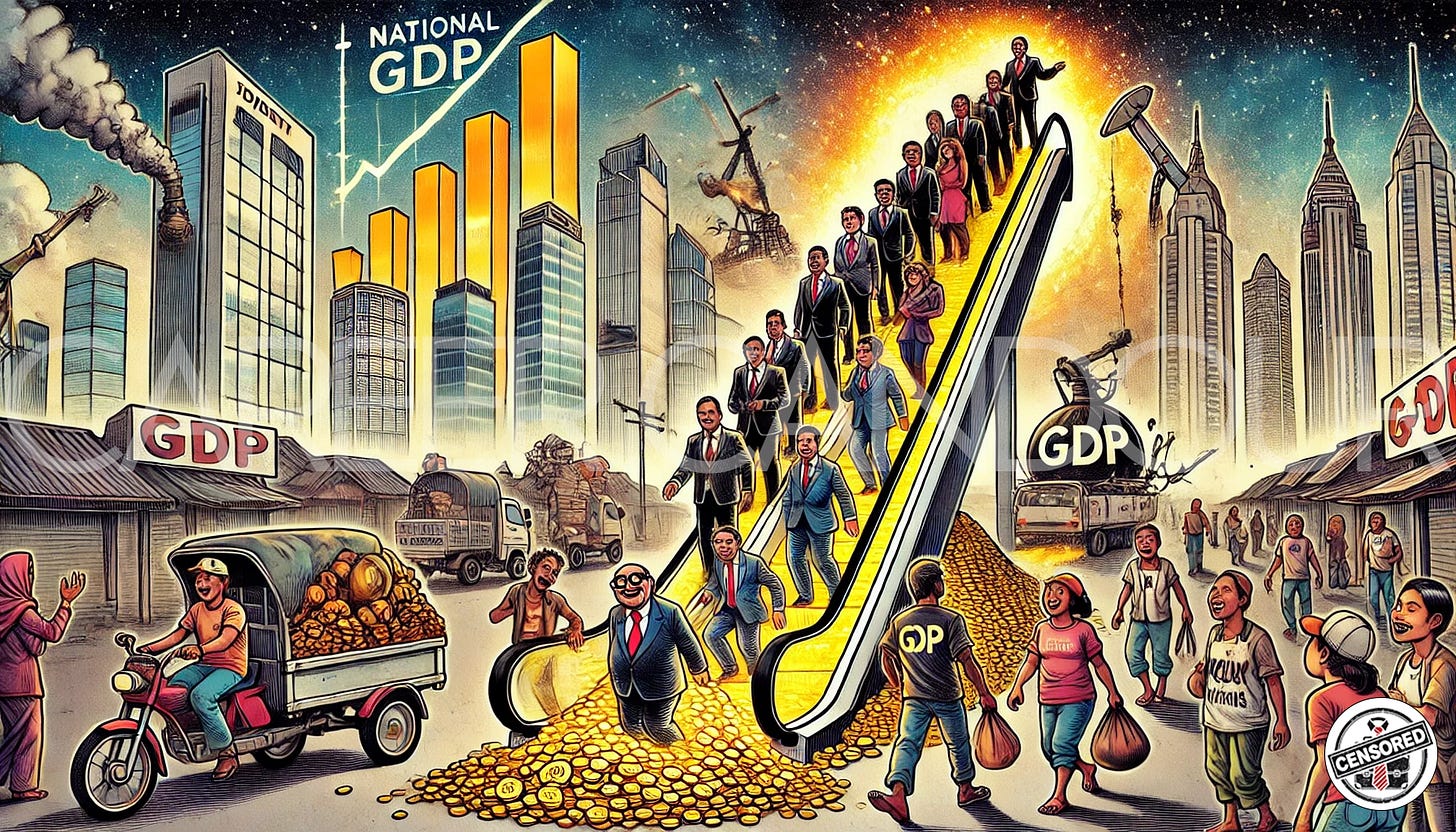

Economic Growth Without Mobility

Indonesia’s growth is real.

Roads are better.

Ports function more smoothly.

Consumption persists.

The state spends heavily and visibly.

None of this is an illusion.

The problem lies in where that growth comes from and what it produces in terms of work.

Much of Indonesia’s recent expansion is driven by sectors that are capital intensive rather than labour absorbing.

Commodities dominate.

Downstreaming projects absorb billions in investment but employ relatively few people.

Megaprojects create bursts of activity, then move on.

Government programs inject money into the economy, but often through channels that prioritise scale and speed over productivity.

Manufacturing, the sector that historically built middle classes across East Asia, has lost ground. Its share of the economy has declined. Factories still exist, but they are fewer, more automated, and less willing to absorb large numbers of low or mid skill workers. Formal job creation lags behind population growth. Informality expands to fill the gap.

The economy settles into a peculiar balance. GDP rises. Unemployment stays low. Wages barely move. Social mobility stalls. People are working, often very hard, but they are not progressing.

Automation, when it arrives, does not lift workers into better roles. It trims labour at the margins and pushes displaced workers into an already saturated informal sector.

In this context, programs like Makan Bergizi Gratis reveal a certain quiet brilliance. They are labour intensive. They are difficult to automate. They create low skill jobs in kitchens, logistics, and distribution across the country.

What they do not do is build ladders. They manage the consequences of an economy that grows without creating credible paths upward, and in doing so, risk making that condition permanent.

Leaving Without a Plan

It helps to separate two very different impulses that often get lumped together under the same migration chatter.

The first is strategic migration.

Nurses learning Japanese to work in hospitals.

Engineers heading to Singapore with contracts in hand.

Students going to Europe with a degree plan and a return option.

This is deliberate, and selective. It is a bet on skill, trajectory, and time. Most countries produce people like this. It is not a sign of failure.

The second impulse is existential migration. Leaving not because there is a better plan elsewhere, but because staying feels like running in place. No clear pathway. No believable timeline. Just the sense that movement itself is preferable to stagnation. Even if that movement is lateral… or worse.

“Kabur Aja Dulu” exists between these two. At times it’s a sign of ambition and frustration with limited domestic opportunities. Other times, it’s exhaustion dressed up as freedom. The danger is not that people want to leave. It is that many no longer care where they go, as long as it is not here.

This is where Cambodia becomes concerning.

Cambodia is not up. It is not the next rung on a global career ladder. And yet, for some Indonesians, it registers as an option. Not a good one. Not a safe one. But an option nonetheless.

That is worth paying attention to.

When people migrate to climb, the system is working imperfectly but recognisably.

When people migrate simply to escape the feeling of being stuck, the issue is structural.

It suggests that the domestic economy is failing to offer not just good jobs, but believable futures.

Indonesia is not collapsing.

Indonesia is not failing.

Indonesia is not doomed.

But Indonesia’s job market, once you step outside the narratives, is far weaker than we are comfortable admitting.

It’s a market that produces work without futures, income without security, and growth without ladders.

It’s a market where being called “middle class” often means standing still rather than moving forward.

It’s a market where a scam compound in Cambodia can briefly register as a step up.

That should unsettle us.

The gap between the story and the experience has grown too wide to ignore.

You can sell eight percent growth targets.

You can brand 2045 as golden.

You can feed children, build roads, launch programs, and confidently announce milestones.

But none of that answers the practical question most people are asking.

Can I build a life here?

Not survive. Not cope. Build.

Until the average Indonesian can look at their domestic job options and answer that question honestly with yes, the narrative will keep cracking at embassy gates, at border crossings, in the aftermath of scam centres and failed migrations.

The most dangerous thing of all is not anger.

It is resignation.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we advise companies operating in Indonesia on building credible career ladders. Contact us to rethink job architecture, skills pathways, and workforce sustainability in a changing economy.