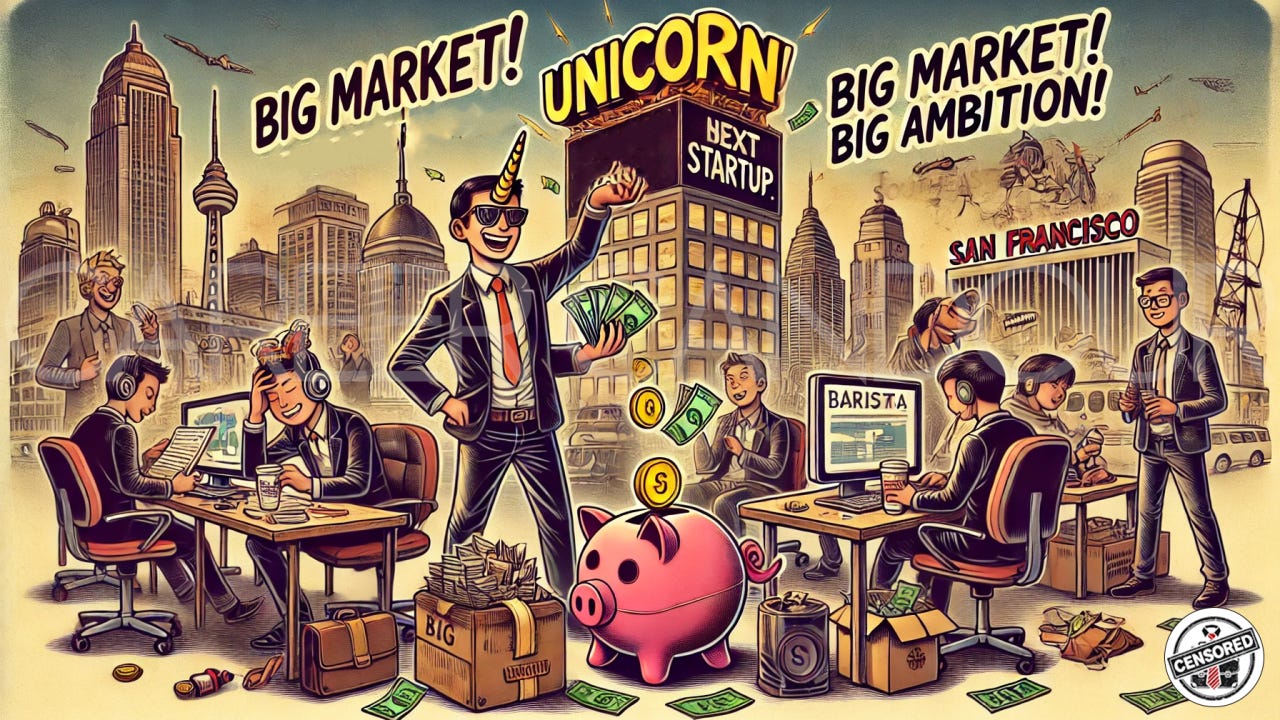

Can You Build a World-Class Tech Company While Paying Jakarta Wages?

Big dreams meet budget constraints. Why startups in Indonesia and beyond must rethink their talent, structure, and growth playbook.

Spend a week in Southeast Asia’s tech scene and you’ll hear the same ambitious chorus:

“We want to build a world-class tech company from right here in Jakarta.”

It sounds bold, modern, and visionary. There’s a well-designed pitch deck, a stylized TAM slide borrowed from someone's Y Combinator application, and a leadership team that looks impressive on LinkedIn. But scratch the surface and it’s often just one overworked generalist wearing five hats, a couple of fresh grads given impressive-sounding titles, and an outsourced dev team. All operating from a shared office space that smells of fried chicken and bubble tea.

The ambition isn’t the problem. The economics are. You can't consistently demand Google-caliber strategy from people making $900 a month and still juggling six jobs internally because you’re too lean to hire more. This isn’t a jab at Indonesia, or any emerging market. It’s about confronting the mismatch between what we wish we could do and what the structure actually allows.

When founders and investors ignore that disconnect, what follows isn’t innovation. It’s disillusionment. It's time to talk about what happens when the dream of global tech supremacy runs straight into local budget constraints.

Great Talent Is Everywhere, But It Leaves

Let’s get one thing clear before the finger-pointing begins: raw talent is not the issue.

Indonesia produces sharp, ambitious, multilingual professionals who know how to hustle. They’re adaptable, globally aware, and capable of learning fast, especially when thrown into the chaos of an early-stage company. They aren't short on intelligence, work ethic, or creativity. What they’re short on is incentive to stick around.

Because the best of them? They leave.

They go where the money is better, the teams are stronger, and the work is respected. In Singapore or Australia, they’re better compensated and surrounded by people who know what "best practice" actually means, and where performance reviews aren't code for politics. Over there, output matters. In many local environments, tenure still trumps impact.

Why grind in Jakarta for a modest paycheck and a fancy title that comes with no mentorship, no equity worth mentioning, and no budget to execute anything meaningful?

It’s not some tragic brain drain. It’s simple math. The return on talent is mispriced.

And if you want to keep your best people, you're left with two equally painful options: overpay them and destroy your cost structure, or underpay them and accept that they're halfway out the door, quietly taking Zoom calls during lunch breaks.

You can try to dress it up, but this is the economic equivalent of asking a Michelin-level chef to work in a food court. You might get a meal out of it, but they won’t stick around to wash the dishes.

Titles Are Cheap, But Execution Isn’t

In many early-stage Indonesian startups, the easiest way to fill the gap between ambition and budget is to hand out big titles. You can’t afford to pay someone like a VP, so you call them one instead. It’s a form of compensation that costs nothing and looks impressive on pitch decks and company LinkedIn pages. Investors see a “Chief Growth Officer” and assume a track record. What they actually get is someone who just figured out how Meta Ads Manager works.

This isn’t about dunking on individuals. It’s about context. The market is still young. Most people haven’t had the chance to work under strong leadership or go through multiple startup cycles. There are few mentors, fewer proper onboarding processes, and almost no real frameworks for how to lead product, scale teams, or run tech at scale. So everyone learns on the fly. Sometimes that works. Often it doesn’t.

The problem isn’t that titles are inflated. The problem is expectations become misaligned. When someone with two years of experience becomes a “VP of Engineering,” you start expecting them to act like one. That includes system architecture, team building, velocity tracking, roadmap planning, and probably a little DevOps on the side. In reality, they’re still debugging legacy code and figuring out how to manage their first intern.

The bigger the gap between the title and the actual capability, the more execution suffers. Deadlines slip. Products underwhelm. Technical debt builds like sediment in an old pipeline. People burn out trying to live up to roles they weren’t trained for.

Eventually, you get a startup with all the labels of a Silicon Valley operation and none of the machinery. Shiny job titles can make a company look grown-up from the outside. But inside, it’s still figuring out how to walk.

Unit Economics Don’t Lie (Even If Pitch Decks Do)

This is where things start to fall apart, because the math refuses to cooperate. Let’s say you go all in. You raise a decent round, get some buzz, and decide it’s time to “professionalize.” You hire a $6,000 per month product manager and a $7,000 designer, both with impressive résumés and actual opinions about design systems. It feels like a turning point.

But then you look at your customer base. Most of them are paying $1 per month, or nothing at all, in a market where disposable income is limited and loyalty is fickle. The numbers stop making sense. Your cost to acquire a user quickly exceeds what that user could ever return. You’re spending like a global player in a market that simply doesn’t give you the margin to do so.

This is structural economics colliding with startup optimism. The pitch used to be about scale and revenue. Now it’s about engagement and "strategic runway." Translation: you're bleeding cash, but some people are still opening the app.

This is the reality many founders eventually run into. You can’t afford the team you need to build a category-defining product, and the team you can afford lacks the experience to take you there. It’s a slow, uncomfortable squeeze. Every new hire feels like a risk and every funding round feels like a delay rather than a step forward.

Some startups solve this by staying lean, serving a narrow market really well, and never pretending to be more than they are. Others expand regionally, fast, trying to find paying users in Singapore or Malaysia to subsidize product development in Jakarta.

The worst path is denial. Building like you're in San Francisco, when your unit economics scream otherwise.

We Romanticize “Emerging Markets” to Avoid Hard Truths

“Emerging market” is one of those phrases that sounds loaded with potential. It evokes growth, opportunity, and the chance to be early in something big. It’s startup catnip. Founders say it with pride. Investors put it in slide decks. Everyone nods enthusiastically.

But underneath the optimism, it often functions as a way to gloss over inconvenient realities. It’s a polite way of saying, yes, there are structural issues, but let’s not talk about those right now. Instead, we hear about grit, resilience, and how “mobile-first” the region is. That’s fine as far as inspiration goes. Less fine when it starts replacing strategy.

Yes, Indonesia is large. Yes, people have smartphones. But scale on paper doesn’t always translate to scale in monetization. Low revenue per user, patchy logistics, unreliable infrastructure, and uneven tech literacy are all part of the real picture. You can’t build the next Shopify in Surabaya without acknowledging the hurdles that come with it.

When we lean too hard into the emerging market narrative, we create a gap between expectation and reality. That gap is where employees burn out, founders run dry, and investors become quietly disappointed.

It’s not enough to romanticize the hustle. We also need to accept the constraints.

If we don’t, we end up selling a dream that doesn’t hold. Employees are promised rocket ships and handed duct-taped go-karts. Founders feel pressure to go global before they’ve even figured out local. And the ecosystem learns to overpromise and underdeliver as a survival mechanism.

The upside is real. But so are the limits. And if we want to build lasting companies in these markets, we have to stop pretending they’re something they’re not. Ambition is good. Delusion is expensive.

This isn’t a takedown of Indonesia’s tech ecosystem. It’s a reminder that ambition without context quickly turns into frustration. Dreaming big is necessary. It fuels innovation, inspires teams, and moves industries forward. But when those dreams ignore structural realities like compensation gaps, skill development bottlenecks, infrastructure limitations, they become counterproductive.

You can’t shortcut your way to global competitiveness by giving inflated titles and hoping for the best. You can’t build a billion-dollar business with a team that's paid in startup equity and motivational quotes. Talent needs investment. Strategy needs grounding. And success needs an honest read of the playing field.

Being realistic doesn’t mean giving up on big outcomes. It means approaching them with eyes wide open. You want world-class design? Pay for it. You want sharp execution? Coach and train for it. You want long-term retention? Offer purpose, growth, and dignity.

Indonesia has all the ingredients to build meaningful, durable tech companies. But the market is still growing into itself. There’s no shame in that. What matters is building in a way that fits the market’s stage, not someone else’s playbook.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we work with clients to build the right structure, capabilities, and leadership from day one. Contact us if you're serious about growth, and we'll help you get serious about who’s in the room.