ICOR, Weda Bay, and the Math of Making Things Work in Indonesia

Discover how Weda Bay defies Indonesia’s investment inefficiency, what drives its success, and the challenges of scaling it.

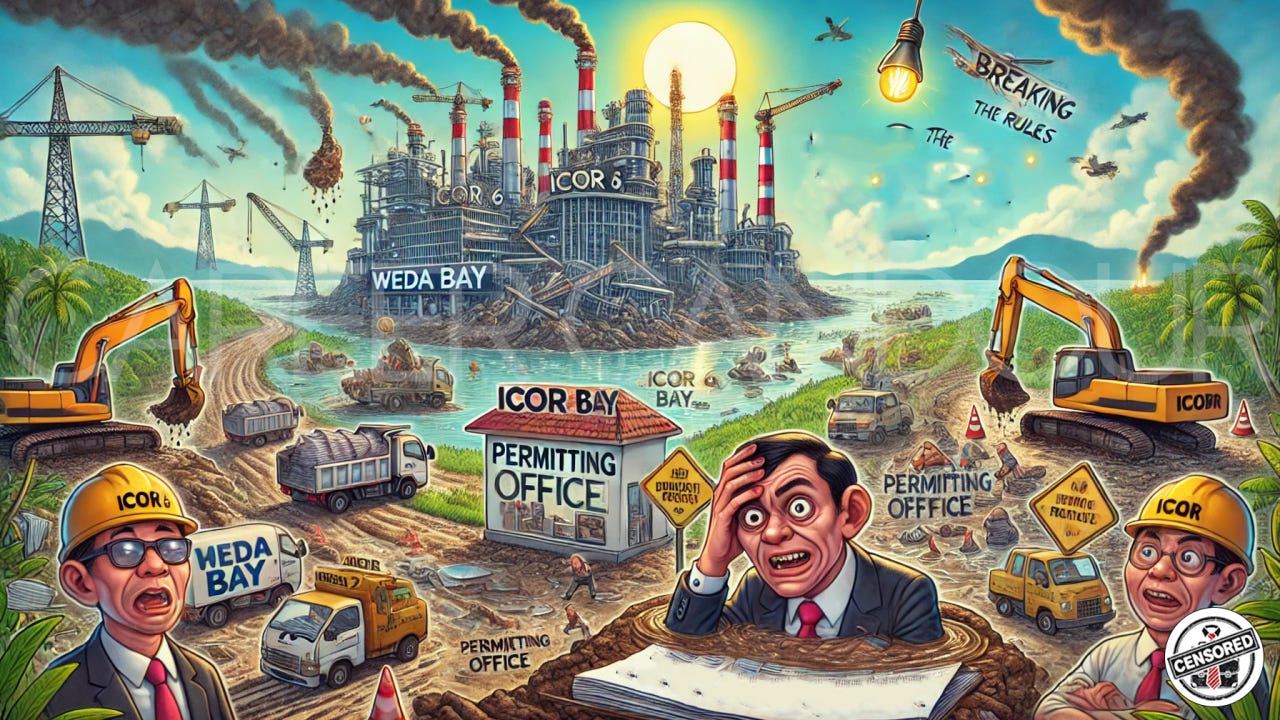

Once upon a time, something peculiar happened. While Indonesia’s national ICOR (Incremental Capital-Output Ratio) hovered at 6.2, signaling that investment is mostly a faith-based activity, a curious little industrial zone named Weda Bay went ahead and reported an ICOR of 2.

Two. As in, you put money in, and something productive actually comes out. It’s the kind of figure that makes bureaucrats blush and economists suspicious. In a country where capital formation is usually packed with delays, and inefficiencies, Weda Bay’s performance looks vaguely un-Indonesian.

This naturally sparks uncomfortable questions.

What’s the secret sauce?

Did someone skip the red tape?

Can we replicate this across the country like a national chain of low-ICOR franchise outlets?

The answers are nuanced. In theory, yes. In practice, well… let’s just say that not every district has a port, power plant, and a joint venture with Tsingshan on speed dial.

Still, Weda Bay demands attention. It’s too productive to ignore and just mysterious enough to romanticize.

Weda Bay: Where Capital Actually Begets Output (?!)

The Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) has done something rare in Indonesia: it invested a truly massive amount of capital (approx. US$16 billion) and got something in return. A lot, actually. Officials report over US$8 billion in annual exports, mostly from nickel products. That gives Weda Bay a rough ICOR of 2.

This is not normal. The secret lies in:

Co-location and coordination. Everything is stacked together in one neat industrial zone: mines, smelters, chemical facilities, port, housing, and even its own power supply. It’s like a capitalist compound, optimized for speed, output, and minimal excuses.

The Tsingshan effect. The Chinese giant brought in proven smelter templates (RKEF and HPAL), plopped them down and ramped up production almost immediately. No grand innovation. Just speed and repetition.

Skipping a national pastime of waiting for PLN. With captive power and its own deep-sea port.

Even permits are streamlined through a “single-window” model.

In short, Weda Bay is aggressively off-script for the typical Indonesian investment experience. And that’s what makes it both fascinating and, aggressively un-Indonesian in the best way.

Meanwhile, in the Rest of Indonesia… ICOR = ?

While Weda Bay cranks out GDP like a well-fed furnace, the rest of Indonesia continues its love affair with expensive inputs and underwhelming outcomes. In 2021, the country’s ICOR soared to 8.. By 2022, it had cooled slightly to 6.2, which still reads like a cry for help in the language of macroeconomics.

The core issue? We invest. Oh, we really invest. But what we get is a sort of polite, underwhelming growth. Enough to save face at summits, not enough to move the needle.

We build buildings, not brains. About 64% of investment goes into concrete and construction. Machinery, tech, and R&D? Just a humble 16%. Think of it like buying dumbbells but never exercising.

Red tape meets jungle tape. Land acquisition. Permit delays. SOEs acting like mini-empires. Your average infrastructure project here takes longer to birth than a baby elephant.

Pungli and ormas and other fun friends. Investors often pay a second tax (the unofficial kind) to get local buy-in. Sometimes it’s an NGO, sometimes it’s just your neighborhood extortion squad.

Logistics costs that insult physics. Up to 24% of GDP at one point (thanks to being 17,000 islands and counting). Even now, at 14%, we’re paying more to move rocks than to mine them.

In a decentralised democracy, coordination is a luxury item. Which is why ICOR = 6+ is basically Indonesia's economic love language.

So Can We Just “Weda Bay” the Whole Country?

It's the perennial policy fantasy: if one thing works, scale it until it breaks. In Indonesia, this usually starts with someone pointing at Weda Bay and saying, “See? Just do more of that.” As if national industrial transformation is a matter of Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V.

The dream has a seductive clarity. Build more Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Give them all single-window permits. Attract foreign capital. Pour in smelters. Watch exports climb and ICOR drop like magic. Cue applause. Maybe even a cover story in The Economist.

But reality is less photogenic.

Weda Bay works because several things aligned at once:

Globally strategic mineral

Reliable offtake partners

Pre-fab EPCs

A local setup that tolerates trade-offs others might flinch at.

There’s no real estate speculation here. No leisure resorts. Just metal, power, and speed.

You cannot build that model in, say, Bali, and expect it to produce battery-grade nickel or capital efficiency. Nor can you inject it into fintech or agritech and get similar returns. This isn’t an “economic model” in the traditional sense. It’s a bespoke industrial machine that happens to fit its niche almost perfectly.

Yes, Indonesia can and should build more Weda Bays, in Morowali, Obi, and beyond, but national ICOR won’t fall just because someone draws more SEZ boundaries on a map. You’d need nickel reserves in Java, Chinese EPC contractors in every district, and permitting systems that function like, well, systems.

Until then, Weda Bay is an outlier. A shiny one, sure. But an exception pretending to be a strategy.

The Seizure Heard Around Halmahera

Just as Weda Bay was polishing its reputation as the crown jewel of Indonesian industrial policy, the forestry task force showed up. Armed with clipboards and a legal clause from 2007, they announced the seizure of 148 hectares inside the Weda Bay concession. It wasn’t the mine itself. It wasn’t the smelter. It was, as they politely explained, a quarry. But it was the wrong kind of quarry.

The issue? No IPPKH (translation: Indonesia’s official forest conversion permit). In other words, the company had the mining license, the export permits, the investors, and the multi-billion-dollar infrastructure... but not the paperwork for that hill over there. So, naturally, it was seized.

This is what happens when the most efficient ICOR-generating zone in the country is still subject to a regulatory system that functions like a choose-your-own-adventure novel written by three ministries at once.

Officials insist the impact is minor. Just a quarry. Nothing to worry about. Business as usual. But the symbolism was hard to ignore. If even Weda Bay can get tripped up by a permit, what happens to the lesser zones, the ones without French co-investors and global demand?

It sends a clear message to anyone thinking of replicating the Weda Bay model: efficiency is good, but permits are better. Or at least more durable. You can deliver exports, jobs, and a tidy ICOR of 2, but forget one line of paperwork and suddenly you’re front-page news.

Let’s not pretend this is normal. Weda Bay is the exception; a rare collision of geology, foreign capital, standardized engineering, and just enough regulatory flexibility to get things moving before anyone asked too many questions.

Yes, it delivers. Yes, it has an ICOR that makes policy planners weep with joy. But pretending this is easily replicable across a country of 38 provinces and 17,000 islands is a bit like assuming you can run a marathon because you once jogged to catch a train.

If Indonesia wants to drop national ICOR to 4 by 2029, it needs:

Logistics reform that doesn’t die in committee,

Human capital that actually matches industrial ambition,

A permitting regime that doesn’t rely on surprise inspections to function.

Weda Bay should be studied, not worshipped. Admired, but not mistaken for a policy playbook that applies to agriculture, tourism, or tech.

So look east. Take notes. Ask questions. But don’t assume it scales just because it sparkles.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we offer expert guidance to optimize projects, manage regulatory complexity, and unlock value in Indonesian markets.. Contact us to navigate investment opportunities and industrial strategy in Indonesia.