The Southeast Asian VC Money Drought (That Isn’t Actually a Drought)

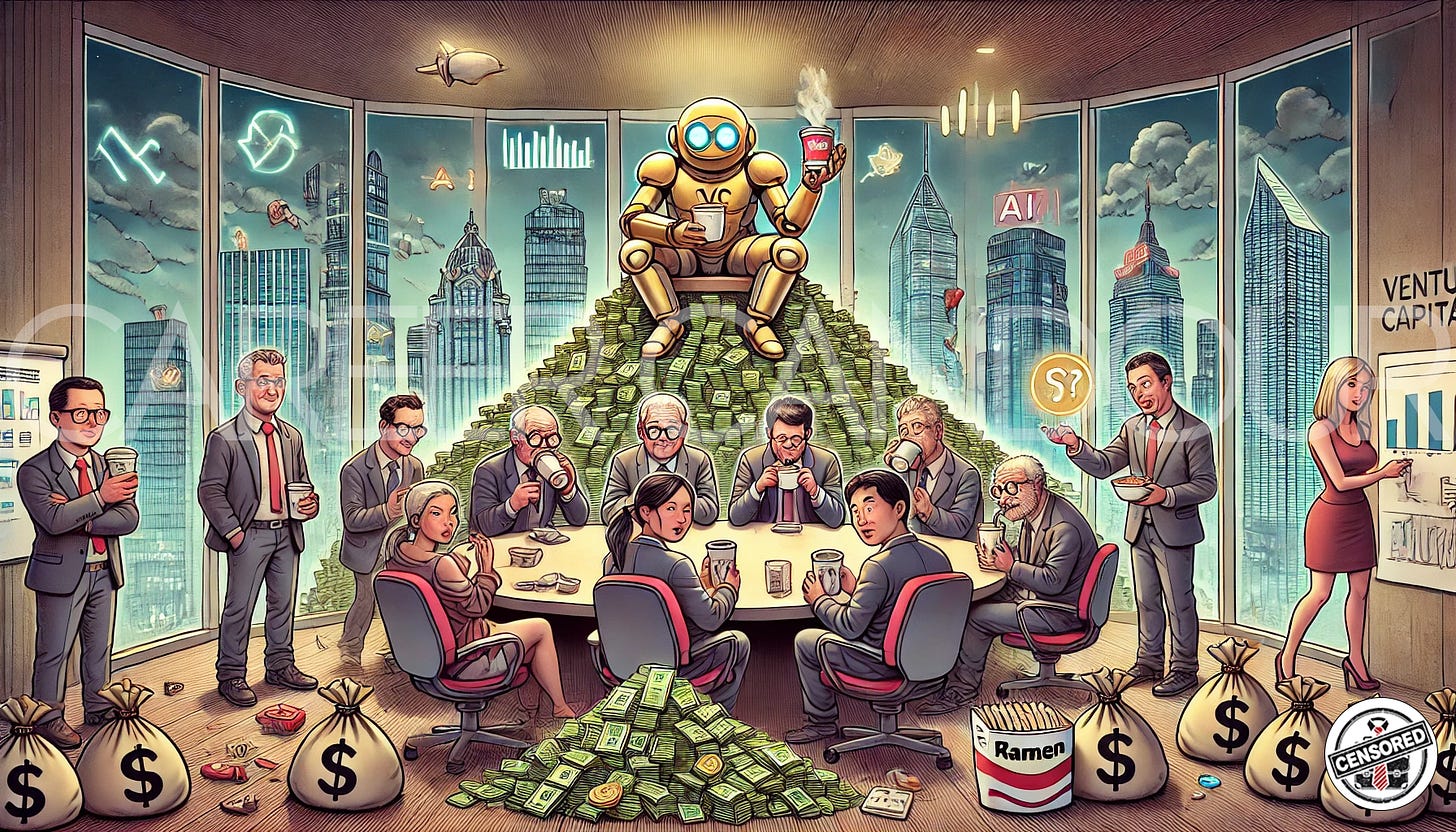

Startups blame capital scarcity. The data says otherwise. Here's why VCs in SEA are sitting on money, and who they’re choosing to fund instead.

Ask a founder in Southeast Asia why they haven’t raised their round, and you’ll get the same same sigh, followed by a confident shrug each time:

“Bro, the VCs are broke.”

It’s a comforting parable, passed from incubator to incubator. In this story, VCs are helpless, bankrupt monks who spent all their money in 2021 on scooter apps and P2E games, and now roam the region unable to fund even a seed round.

This is nonsense.

The truth? VCs have money. Lots of it. Billions, actually. But the post-2021 world has made them careful, calculating, and slightly allergic to anything that smells like burn-before-revenue. The bank vault isn’t empty, but the key now comes with a background check, three-month diligence cycle, and a demand for actual business fundamentals.

Globally, dry powder has piled up. Capital is abundant, but deployment is restrained. So no, the system isn’t broken. It’s just cautious, sober, and very much still rich. Which is somehow more frustrating, isn’t it?

A World Swimming in Cash but Too Anxious to Jump In

Globally, VCs are not hurting for cash. In fact, they are drowning in it. The industry is sitting on an estimated US$652 billion in unallocated venture capital (Q1, 2024), and US$2.5 trillion in broader private capital (Q2, 2025), according to people who count these things for a living. There’s also a significant sum of unspent 2021-era capital lingering in funds that were raised at the height of collective mania.

So why isn’t this money being put to work?

In 2021, capital deployment was a speedrun. If you had a deck, a dream, and a domain name, you were in. But now, everyone’s in recovery. Investors were burned by inflated valuations, nonexistent unit economics, and founders without business models. Funds raised during that time are now afraid to write checks.

IPOs? Scarce. M&As? Rare. Decacorn liquidity events? Uncommon. Without exits, returns are theoretical. And with LPs demanding real outcomes instead of imaginary multiples, GPs are choosing to wait and pray to the exit gods.

LPs, once drunk on ZIRP-era optimism, now want cash flows, clarity, and credible paths to profit. In response, VCs have evolved. They perform actual due diligence and move at a pace reserved for glacial erosion.

The result is a world rich in capital but governed by caution. The vault is full, and the door is open. But the finger is still hovering over the “deploy” button, waiting for someone, anyone, to blink first.

The Southeast Asia Situation: Billions in Dry Powder

Word on the street is that Southeast Asia’s VCs are broke. Struggling. Penniless. But the actual data disputes that.

In reality, there’s at least US$7.4 billion in ASEAN-focused VC dry powder (Q2 2023), just sitting around, patiently waiting. Add to that the roughly US$6 billion in 2021-raised SEA funds that still haven’t been fully deployed, and you begin to realize the vault is stocked. Throw in global funds with SEA mandates, and it turns out the region isn’t short on capital.

Why isn’t it flowing like it used to? Because the Southeast Asian startup scene experienced a post-2021 whiplash. Funding fell 70 percent from its peak, early-stage deals shriveled up, and capital became cautious. You can still get in, but only if you’re AI, profitable, or somehow already famous.

Secondary markets? Also not helping. In Southeast Asia, secondary deals are… let’s say “culturally rich.” We have:

Buyers who negotiate for 18 months

Sellers who “reconsider” a week before signing

Valuations that live in alternate universes

Legal documents that seem written to confuse both parties.

And now? VCs are still investing, just in a very specific kind of founder: seasoned, vertical, and allergic to burn. If your pitch has the scent of 2021 optimism, they’ll politely nod, then redirect their attention to the AI-powered logistics startup with actual revenue.

So yes, to many founders, the money feels gone. But it’s not. It’s simply hiding in plain sight.

Why VCs Can’t Actually Sit on Money Forever (Even If They Wanted To)

Contrary to the popular narrative that VCs are gleefully sitting on stacks of cash, the reality is far less glamorous. Venture capital doesn’t work like that. VCs can’t hoard indefinitely. They have timers ticking in the background. And when those timers run out, things get awkward.

Most VC funds have three to five years to deploy the capital they’ve raised. Not spend. Deploy. That means picking companies, writing checks, and building a portfolio that doesn’t look like it was selected by a Magic 8-Ball. Wait too long, and they risk ending the investment period with an under-diversified mess and a bunch of LPs asking, “So… what exactly did we pay you to do?”

Imagine telling your investors: “We didn’t invest your money. We also didn’t return anything. But would you mind wiring us another $200 million?” VCs who don’t deploy hurt their track record, their reputation, and their next fundraise. LPs are forgetful in bull markets, but not that forgetful.

Valuations normalize. Rates fall. Exit markets re-open. Suddenly, everyone wants in again. The slow movers find themselves behind. The founders they passed on raise elsewhere. The funds that waited too long get stuck explaining why they missed the next wave.

So yes, VCs look cautious now. But they are under pressure. The cash must move. The clock is ticking. And no one wants to be the fund that sat out the rebound.

Not a Drought, But a Redistribution of Who Gets Funded

What we are witnessing isn’t a funding winter; it’s an aristocratic reallocation. The capital is still flowing, just not toward you, your friends, or anyone who hasn’t yet done a TEDx talk or raised a Series B from Sequoia.

This is the modern VC climate: selective, concentrated, and increasingly allergic to anything that doesn’t come with metrics and a management team that already made someone rich. Capital is moving toward AI infrastructure, data centers, deep tech, and anything that sounds like it belongs in a Temasek presentation. If your pitch can be explained in under two slides to a sovereign wealth fund, you might just get a second meeting.

This isn’t a pullback in total capital. It’s a drastic narrowing of who qualifies. The pendulum has swung from “growth at all costs” to “how fast can you get to EBITDA, and please don’t say 2027.”

In Southeast Asia, this is compounded by structural issues. Yes, we have rapid digital adoption and a young consumer market. What we don’t have is a robust track record of billion-dollar exits or liquid secondaries. The result?

Global LPs are still cautious.

Local VCs act accordingly.

Founders are left holding valuations no longer backed by demand.

So, no, there’s no drought. The money is available, but no longer without expectations. Show them results. Show them discipline. Show them you can survive beyond the first party round. Then, and only then, might you be allowed to taste the capital you keep hearing about.

VCs in Southeast Asia are not broke. They are sitting on billions in dry powder, watching the market, running spreadsheets, and evaluating.

They are not withholding money out of cruelty or laziness. They’re cautious because the last cycle left them with scars and overpriced cap tables. They are managing expectations, risk, and, most importantly, their reputations. Deploying capital recklessly in this environment would be malpractice. So they wait.

It’s easier, of course, to say “VCs just don’t have money.” That shifts the blame. It saves you from interrogating your metrics, your model, your assumptions. And while that explanation is soothing, it’s also wrong.

The capital is there. It is being deployed. Just not indiscriminately. Founders who recognize this (and adjust) will find the money. The rest will keep mistaking selectivity for scarcity.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we support growth-stage companies in building the kind of talent and scale narratives that actually get funded in today’s selective market. Contact us to build leadership teams and hiring strategies that clear these standards.