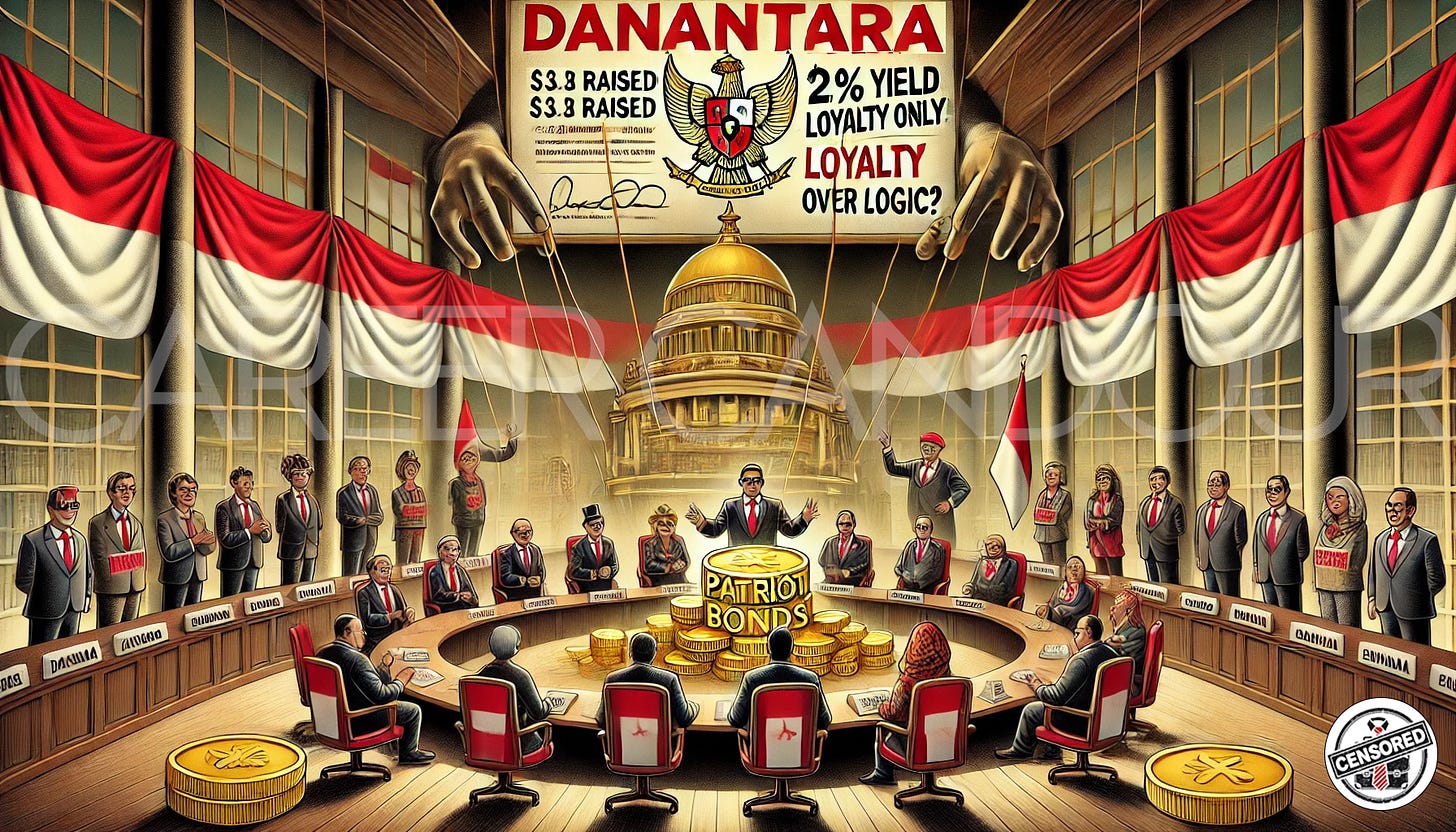

Patriot Games: Indonesia’s New Super Fund Wants Your Money… for the Nation, of Course

Danantara is selling 2% bonds to tycoons in the name of patriotism. We take a look at the debt, the drama, and the déjà vu of state-led finance.

Indonesia has just pulled back the curtain on its latest act in the theater of state-led capitalism: Danantara, a sovereign wealth fund-slash-holding company-slash-flag-waving-symbol of national ambition. It comes cloaked in the language of progress, cradling a dream of economic sovereignty in one hand and a suspiciously soft-yielding Patriot Bond in the other.

Love your country? Good. Show it by lending it your money at a cool 2 percent interest, locked in for several years. Yes, you read that correctly. Not 6 percent, like regular government bonds. Not 4 percent, like your cousin’s fixed deposit. Two. In rupiah, no less. In return, you get credibility, proximity, and possibly an extra smile at next week’s state dinner.

The fund’s leadership has wrapped it in the language of national pride and “shared sacrifice,” which is always more effective when the sacrifice is someone else’s. What’s less clear is how this fits into any traditional understanding of sovereign wealth. There are no foreign reserves involved, no public prospectus, and no explanation as to why investors should happily accept negative real yields.

Still, the bonds are reportedly oversubscribed. Maybe patriotism really does pay. Just not you, the investor.

So what are we dealing with here? Is this financial innovation, or a bond-shaped political IOU with questionable economics and unsettling precedents?

Patriotism: Now with a Maturity Date and Coupon Clause

The rollout of Danantara’s so-called “Patriot Bonds” didn’t so much resemble a capital markets transaction as it did a national loyalty quiz for the wealthy. It wasn’t “Would you like to invest?” but rather “How much do you love Indonesia?” The question was rhetorical. You love Indonesia, therefore you will buy.

You won’t find these bonds in the open market or on your brokerage app. This was a private placement, reserved for the familiar handful of conglomerates and dynasties who regularly orbit the state’s gravitational field. Names weren’t announced. No roadshows, no pitch decks. Just a 2% yield, a whisper in the right ear, and a subtle hint that showing up empty-handed might not be… ideal.

According to reports, Rp50 trillion was raised in 24 hours, and the bond was “oversubscribed.” By whom? We don’t know. With what conditions? We don’t know. Will this bond be tradeable, marked to market, or regulated like anything resembling a proper financial instrument? Also unclear.

What we do know is this: you don’t buy a Patriot Bond for the return. You buy it because it’s cheaper than political irrelevance. For the big business families, this is a small donation to stay inside the tent. Your reward is not 2% annually. It’s continued access. Continued invitations. Continued protection.

So no, this wasn’t “buy low, sell high.” This was “buy low, stay visible.” You don’t want to be the only one in the room who didn’t subscribe when the state came calling. Not when those BUMN board seats are being filled.

The Ghost of 1MDB Past: Debt-Fueled Development with Just a Hint of Secrecy

The moment Danantara started issuing bonds without sharing a public term sheet, a use-of-proceeds breakdown, or clarity on guarantees, a chill ran down the spines of regional economists and anyone with access to a Bloomberg terminal. Memories stirred. Somewhere in Kuala Lumpur, 1MDB lit a cigarette and smirked.

To be clear: Danantara is not 1MDB. No Hollywood donations, no suspicious fine art purchases, no disappearing multi-billion dollar transfers (as far as we know). No one from Leonardo DiCaprio’s entourage has been spotted at Danantara HQ. Yet.

But comparisons don’t come from nowhere.

Danantara is raising debt in the name of “strategic projects,” without fully disclosing what those projects are or how they’re being selected.

Reports reference waste-to-energy ventures and some ambiguous “national priorities,” but the details remain unclear.

Buyers aren’t traditional bondholders either. They’re prominent business families with long-standing links to ministries, SOEs, and the kinds of people who know which tenders are coming before the ink dries.

And then there’s the pricing. 2% coupon. If this were a regular market deal, someone would be fired. Instead, it’s being praised as a patriotic act.

Debt isn’t the villain. Most large sovereign investment entities raise debt. 1MDB’s collapse wasn’t because it borrowed, it was because it borrowed without accountability.

Danantara still has time to choose a better path. But its decision to open with a secretive, private-placement bond that defies market logic puts it uncomfortably close to the slippery slope of “just trust us.” If they want to avoid becoming the next regional finance cautionary tale, transparency needs to arrive before the next tranche does.

Sovereign Wealth Fund? Investment Company? Or Something Else Entirely?

What, exactly, is Danantara?

Is it a sovereign wealth fund (SWF), like Norway’s GPFG or Singapore’s GIC?

Is it a state-owned holding company, like Temasek?

Is it a stealth national fundraising mechanism wrapped in a love letter to the homeland?

Let’s look at the evidence.

It doesn’t manage foreign exchange reserves, which most traditional SWFs do.

It’s not funded through oil surpluses, trade windfalls, or gold bullion buried under Merdeka Palace. It is instead funded through state asset transfers, dividends from SOEs, and now, by issuing debt instruments to patriotic billionaires with a low appetite for returns and a high appetite for staying out of trouble.

It owns, manages, and "reforms" SOEs, takes their dividends, and then proceeds to fund projects that just so happen to align neatly with sectors where politically exposed persons have been known to dabble. The projects are dubbed strategic. The connections are labeled coincidental. The paperwork is not available for public viewing.

Unlike Singapore’s GIC, there is no public Santiago Principles compliance statement. Unlike Temasek, there is no transparent investment charter. Unlike Norway’s GPFG, there is no publicly released balance sheet. What we have is a high-conviction national vehicle with low-disclosure habits.

A few optimists have compared Danantara to Israel’s Yozma program. That’s generous. Yozma was a VC fund-matching scheme that helped build a tech ecosystem. Danantara is a state-created, bond-issuing, SOE-controlling investment blob with a boardroom full of appointees and a mandate that shifts slightly depending on who’s giving the keynote speech.

Calling it a sovereign wealth fund is a stretch. Calling it a State-Inspired Financial Innovation, or SIFI, feels more accurate. It may be innovative. It is definitely state-inspired. Whether it’s financially sound remains to be seen.

2% Coupons and the Price of Staying in the Game

Let’s return to the most puzzling feature of Danantara’s bond program: the 2% yield. It’s not just low. It’s the kind of number that makes central bankers smirk and bond traders squint. At a time when Indonesian government bonds yield around 6% and the inflation rate sits above 2.4%, the real return on the so-called Patriot Bond is less than zero. You are not investing. You are politely handing over your cash and hoping it behaves.

And yet, within 24 hours, we’re told the offering was oversubscribed. The speed and scale of interest suggest that yield was never the point. These are not conventional bonds. They are more akin to membership tokens, evidence that you’re still in the room where things happen. At 2%, you are buying visibility, influence, access; the trifecta of business survival in a system where public-private “partnerships” often begin with a phone call and end in a board seat.

In this context, the bond’s function is strategic, not financial. It keeps Indonesia’s industrial aristocracy firmly tethered to the state. It keeps capital close, and competitors further away. And from the government’s point of view, it offers a fast, quiet way to fund projects without wading into the unpredictability of open capital markets.

But there is a danger in confusing loyalty with liquidity. Markets function on pricing signals and voluntary participation. If this bond program becomes more pressure than patriotism, the illusion of stability may start to wobble. The risk isn’t immediate default. It’s the erosion of credibility, the quiet bleeding of investor confidence that happens when markets realize the returns are not the point and maybe never were.

And as history often shows, investor faith is much easier to spend than to earn back.

Danantara is bold. That much is undeniable. It is wrapped in patriotic rhetoric, fuelled by strategic ambition, and positioned as the government’s answer to modern state-led investment. It might even become the economic engine it claims to be. But today, it exists in a kind of high-stakes limbo, where potential and opacity sit side by side and nod politely.

The Patriot Bond program could mark the beginning of something valuable: a sovereign platform that smartly channels domestic and foreign capital into meaningful, long-term growth. Done right, it could modernise SOEs, catalyse industry, and carve out a credible space for Indonesia among heavyweight investment institutions. Done wrong, it becomes a soft-money instrument for elite access, where loyalty replaces returns and the risks are quietly socialised.

For now, the offering’s structure raises fair questions. No public term sheet. No use-of-proceeds breakdown. A 2 percent yield pitched in a 6 percent market. Bonds sold not to the market, but to a select few with surnames that appear on shopping malls and airport terminals. This is not how credibility is built.

To be taken seriously, Danantara must publish, disclose, explain. A proper investment charter. A prospectus. Transparent governance rules. Clarity on guarantees, exits, and obligations. These are not luxuries. They are the price of admission to global respectability.

Until that happens, Patriot Bonds may succeed as symbols of allegiance. But anyone hoping to fund their retirement off them should probably look elsewhere, or at the very least, keep a close eye on the footnotes.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we help clients cut through noise and navigate Indonesia’s political economy with clarity. Contact us for on-the-ground insights that help investors see beyond the slogans and into the fundamentals.