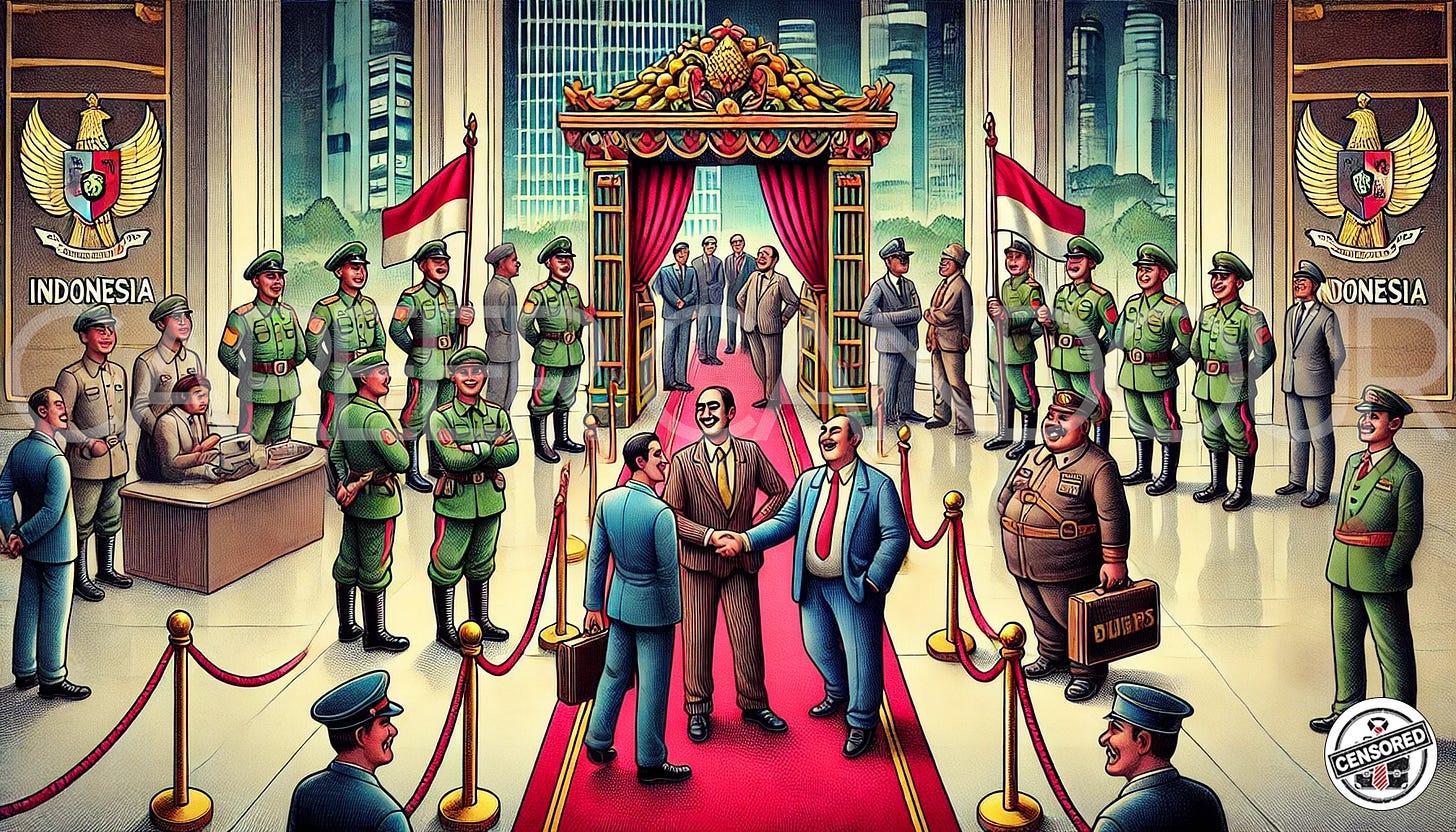

Welcome to the VIP Lounge: How Indonesia Made FDI a Members-Only Affair

Indonesia talks about welcoming FDI, but real investors face control, gatekeeping, and policy traps that keep power firmly in local hands.

Indonesia, at first glance, is the kind of place that makes foreign investors salivate. Endless commodities, a young population, a government that swears it wants your capital, and a growing list of trade expos where officials declare open arms for Silicon Valley’s finest. The surface narrative is polished. Multinationals are courted with charm offensives, investment summits, and a rotating cast of ministers on roadshows pitching green zones and digital ambitions.

But beneath the photo ops and soundbites, a different story unfolds. The real machinery of Indonesia’s economy doesn’t run on foreign capital. It runs on control. Access is doled out selectively, tactically, and usually through a local gatekeeper with the right family name or institutional tie. Try going it alone, and you’ll find yourself entangled in permits, standards, import caps, and a growing list of alphabet-soup regulations.

In 2025, the contradictions stopped even trying to hide. What used to be quiet manipulation in steering investment toward state-owned partners or national champions, has become something closer to policy doctrine. The state smiles for the camera. But the fine print says: invest if you must, just make sure the right people get paid.

How Foreign Investment Gets the Tourist Menu

Foreign investors landing in Indonesia are greeted with ceremony, charm, and a state-curated list of “priority sectors.” Think downstream nickel, solar parks in Kalimantan, and EV assembly zones. There’s usually a press conference. Sometimes a ribbon. Always a minister declaring the era of red-tape-slashing reform. The menu is clean. It promises opportunities. It politely avoids mentioning the black hole of actual implementation.

Because once you try to order something that’s not on the set menu, or serve a product the local giants haven’t signed off on, you’re in for a lesson in what “market access” really means. The 2025 fuel debacle made this crystal clear. Foreign fuel retailers like Shell and BP-AKR saw demand surge after Pertamina fumbled a quality issue. Their reward? The government capped their import volumes and told them to start buying their gasoline from, you guessed it, Pertamina. “Collaboration,” officials called it. Coordination, if you will. The Energy Ministry helpfully clarified: they must agree to it.

The same playbook showed up with Apple. A billion-dollar investment, and they still couldn’t get their newest iPhone certified for sale. Local content rules stood in the way, enforced with a resolve that mysteriously never seems to slow state-backed telcos or domestic assemblers.

It’s not about keeping out bad actors. It’s about keeping control. Preferably via an SOE, a state fund, or someone with a seat at the grown-up table. Everyone else gets the tourist menu: neatly printed, very pretty, but mostly for show.

Indonesia doesn’t reject foreign investment outright. It just wants it filtered, and routed through channels that preserve the balance of power. If your project strengthens the local hierarchy, welcome. If it disrupts it, prepare to coordinate.

Danantara: The Friendlier Face of “Invest Through Us or Not at All”

Danantara arrived in early 2025 with the smooth branding of a reform. A new sovereign wealth fund, they said, designed to streamline state assets and accelerate investment. On paper, it was a move toward sophistication. In practice, it felt more like a consolidation of leverage. Less fund, more funnel. Danantara quickly became the single most important gate through which foreign capital must now pass, especially if the capital in question might ruffle the feathers of local champions.

If you’re eyeing critical sectors, there’s now an unspoken rule: go through Danantara or don’t go at all. Invest in a nickel smelter? You’ll need to coordinate with MIND ID. Energy projects? Better sit down with PLN or Pertamina. Anything resembling strategic assets? Don’t worry, Danantara’s already in the room before you arrive. It’s not a partnership. It’s a chaperone.

The Freeport stake drama made this power shift embarrassingly clear. First, government figures announced that Freeport would hand over 12% of its Indonesian unit “for free” as part of a deal extension. Then, Danantara’s CIO turned around with a reframing. “Unlikely we take it for free,” he said. The message was unmistakable: terms are fluid, depending on who’s speaking and who’s watching.

What Danantara really offers is predictability… for insiders. It gives the state a cleaner channel to mediate deals, apply pressure, and ensure the right stakeholders walk away happy. For foreign investors, it’s a friendlier face masking the same old control logic. You’re still welcome, technically. But don’t mistake this for liberalisation. You’re being asked to participate in an arrangement.

Show up with capital, sure. But expect to share it. And please, bring a partner with good connections. Preferably one who never asks too many questions.

FX Rules, Policy Signals, and the Theater of Economic Sovereignty

In a textbook economy, exchange rates signal investor sentiment, macro strength, and policy credibility. In Indonesia, the rupiah signals all of those things too, just with the added nuance of half a dozen hands quietly adjusting the levers from behind the curtain.

Despite a weakening US dollar in 2025, the Indonesian rupiah still managed to chart its own path downward. It wasn’t just soft. It was Southeast Asia’s worst-performing currency for much of the year. An impressive achievement for a commodity-rich country supposedly in the middle of a green-industrial boom. So what’s the underlying message?

Surprise interest rate cuts. They caught markets off guard and signaled that domestic growth and political pressure were being prioritized over FX stability.

Questions around Bank Indonesia’s independence, a theme that resurfaced just enough to make investors uneasy without ever fully resolving.

100 percent onshore retention rule for export proceeds. Previously 30 percent for three months, this new mandate ensured exporters would keep their dollars inside the system for a full year. A nice way to prop up liquidity on paper. A less nice way to attract foreign capital.

FX policy “adjustments” to enhance stability. Translation: more restrictions if needed, fewer exits if things get messy.

Framed externally as acts of macroprudence, these policies look a lot more like precautionary control mechanisms when viewed from inside the system. Indonesia wants to host capital under surveillance, hold the keys to the vault, and ensure it doesn’t move until officially released. And yes, if possible, do it all while smiling politely and shaking hands at an investor forum in Singapore.

“Self-Sufficiency”: The Flag-Wrapped Fortress of Crony Economics

Indonesia’s long-running love affair with “self-sufficiency” reached its theatrical peak in 2025. Declaring an end to imports of rice, sugar, corn and salt through the rest of the year, Indonesia wrapped itself in nationalistic language. It sounded patriotic. It photographed well. It also made rice more expensive and harder to find.

By the third quarter, supermarket shelves began to feel the squeeze. Premium rice vanished or got quietly rebranded with humbler packaging and higher prices. State logistics agency Bulog rushed to secure domestic supply, but even it had to admit that the numbers weren’t lining up. And when it finally sought permission to import? Silence. The script didn’t allow for that scene.

The irony here is that the stated goal is to protect farmers and the “small guy,” but the structural beneficiaries are anything but small. In reality, this policy keeps well-connected agribusinesses and state procurement arms firmly in control. Market access becomes a political privilege, and import substitution becomes a profitable bottleneck.

This isn’t really about food security. It’s about economic insulation and guarding domestic monopolies from the efficiency and price pressure that foreign competition might bring… dressed as a grassroots movement.

The same logic applies across fuel, fintech, telco, and mining. A few public-facing narratives, a sprinkle of nationalism, and behind the curtain: SOEs, local giants, and political families locking in market share. Meanwhile, foreign investors trying to bring lower prices or better tech are told politely that the market is “sensitive.”

The phrase “supporting the little guy” gets tossed around often. But when the “little guy” owns a shipping fleet and a private jet, maybe it’s time we revisit the definition. Or at least stop pretending this is about the poor.

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve passed the unspoken entrance exam. You now understand that Indonesia’s embrace of foreign direct investment is not rejectionist, just exceptionally conditional. The model isn’t broken; this is the model.

Foreign capital is welcome, as long as it comes with a leash. The ideal investor sets up a joint venture with a well-positioned local partner, keeps quiet about rule inconsistencies, and accepts that final decisions will be made by people whose names don’t appear on your due diligence memo. Preferably over a golf game.

Competition? Absolutely. Just not the kind that puts established monopolies at risk.

Transparency? Of course, but not when it involves sensitive things like royalty hikes, license re-issuance timelines, or why only one importer received quota approval this quarter.

The open secret is this: if Indonesia were to actually open the market, in the truest sense, many of the current winners would no longer be winning. The state knows this. So do the investors who’ve been around long enough to stop taking the brochures at face value.

And so the velvet rope remains. The slogans continue. The system hums. Good luck. And don’t forget your patriot bond.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we work with leadership to map influence networks and align local execution with real market realities. Contact us if you’re navigating talent or market entry in Indonesia.