Indonesia’s Feel-Good Social Survey Finds Everything Is Fine... Please Stop Asking Questions

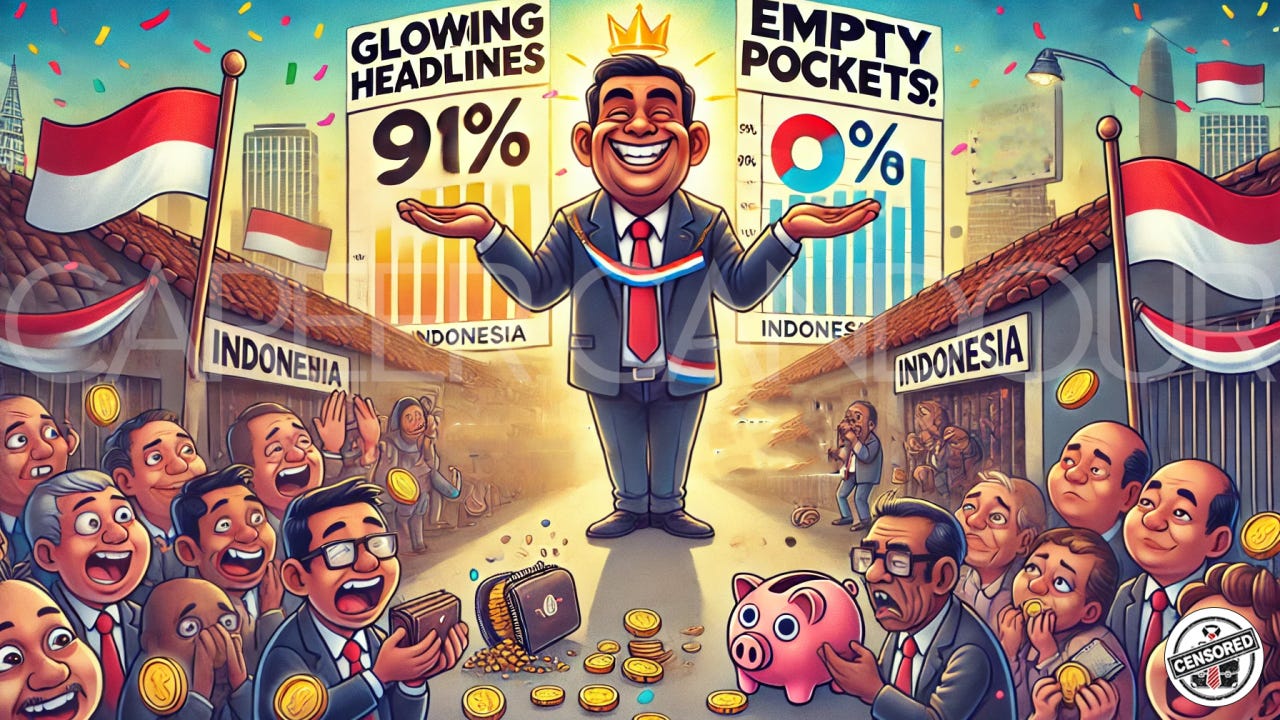

Indonesia’s 2025 social survey shows high trust in leadership despite deep economic hardship. Are people truly satisfied, or is something missing?

If you skimmed the headline results of the Indonesian Social Survey (ISS) last week and thought, “Well, things are looking up,” you weren’t alone. The numbers painted a picture so sunny you’d think the report came with a complimentary piña colada. According to the report,

78% of Indonesians are satisfied with the government.

Trust in the President sits at 90.9%, a number so high it should come with a warning label.

The Vice President? A respectable 81.6%.

The nation’s Quality of Life Index? 65/100, bolstered by solid scores in health, safety, and institutional trust.

The MBG (Free Nutritious Meals) program? Apparently, it’s everyone’s favorite public policy since fried tempeh became a lunchbox staple.

But blink twice and the bottom half of the report tells a grimmer tale.

Nearly 60% of respondents said they had to borrow money because they ran out.

Over 62% of household heads reported the same.

Economic welfare was the worst-performing dimension of the index at just 42.6.

Almost half of households are living on less than Rp2 million a month.

So what gives? Is this optimism? Resilience? Selective amnesia?

It could be gratitude in tough times. Or something else entirely. Either way, there’s an incongruency here worth exploring.

Everyone’s Happy, but Nobody Likes Politics

Let’s start with what might be the most eye-catching number in the entire ISS release: 90.9% of respondents trust the President. That’s political oxygen. It puts him in the same trust bracket as baby pandas and emergency room doctors, and it outpaces nearly every global leader currently in office.

Trailing just behind is the Vice President, with a still-impressive 81.6% trust rating. Not bad for someone who’s barely settled into the national spotlight and hasn’t yet had to deliver any bad news.

But then the cracks start to show.

Trust in the national legislature? 67.2%.

Trust in political parties? 60.8%.

And within that, a blunt 24% say they don’t trust them at all.

Which raises the obvious question: if you don't trust the parties or the lawmakers, how do you end up with so much faith in the people they help elect and empower?

This is a familiar pattern in Indonesian polling: strong personal loyalty to leaders, coupled with broad suspicion of systems. People separate the man from the mechanism. It’s easier to rally behind a familiar face than a faceless committee.

Still, it presents a democratic dilemma. Can a system truly function when the public trusts its outcomes but not its processes? The ISS results don’t answer that question, but they certainly highlight it. In Indonesia, it seems the people still believe in the driver, even if they’re not so sure about the car.

Household Struggles: The Data That Doesn’t Smile

Here’s where the feel-good narrative begins to wobble. While the ISS tells us that Indonesians are largely satisfied and trusting, the economic data from the very same survey quietly tells a much bleaker story.

Start with income.

41.8% of households report living on just Rp750,000 to Rp2 million per month.

6.9% of households who report monthly spending under Rp750,000, or roughly US$49. For an entire household. That’s around the cost of one decent meal at a mid-range café in Jakarta.

Stacked next to these numbers:

59.6% of respondents had to borrow money because they ran out.

Another 62.2% of household heads said they’ve had to borrow just to stay afloat.

And yet, the broader sentiment is one of resilience. Satisfaction with government remains high. So does trust.

Why?

Social desirability bias could be influencing answers; people may soften criticism when talking to a survey enumerator.

Expectations are already low. If day-to-day life has been tough for a while, any minor improvement (like a free school lunch) feel like big wins.

The perasaan aman effect, where relatively high satisfaction in safety and trust, can soften the impact of empty wallets.

But still, at some point the math feels off. If six in ten people are turning to debt to survive, yet satisfaction remains high, the question becomes less about trust and more about what people have learned to accept.

MBG to the Rescue? (Kind of. Not Really.)

One of the standout elements in the ISS report is the soaring popularity of MBG (Free Nutritious Meals). Designed to tackle child malnutrition and boost school attendance, MBG is a communications success story.

The numbers are impressive by any metric:

67% of respondents recalled the program without being prompted.

When prompted, 89% recognized it.

82% said it was beneficial.

That’s a remarkable level of penetration for a program still in its early phases. It’s clear that MBG is resonating across communities. The visibility of daily meals, delivered to children in uniform, creates a tangible connection to government action.

But dig just a little deeper, and the limits of MBG’s impact begin to show. Even the ISS itself acknowledges that the program has only slightly reduced household expenses, and hasn’t meaningfully lifted financial burdens. For many families, the difference between economic strain and stability still lies in wages, prices, and job security.

That said, the political utility of MBG is undeniable. It’s an easy win for a new government. It tells voters: “We see you, we’re doing something.” And in Indonesia’s political context, being seen is often more powerful than the actual outcome.

So yes, MBG is helpful. It’s also limited. Whether it becomes a foundation for long-term progress or simply a well-marketed policy moment depends entirely on what comes next.

So... Is It All Real?

Here’s the million-rupiah question: Are these numbers real?

On the surface, yes. The Indonesian Social Survey (ISS) follows the usual standards.

A sample of 2,200 respondents,

Spread across 38 provinces,

Drawn using multi-stage random sampling, and

Packaged with a ±2.5% national margin of error.

Methodologically, this is what a legitimate survey looks like.

But the devil is in the fine print, which in this case is missing.

There’s no prior ISS time series, so we can’t compare these numbers to their own historical data. Without trendlines, we’re left interpreting a single frame without knowing what came before or what’s typical.

There’s no published technical annex, meaning we have no visibility into how the indices were calculated, what the weighting structure looked like, how “trust” was defined, or whether something as basic as household spending was measured per capita or per family.

Then there’s the matter of the 90.9% presidential trust rating. That’s a very high number in any democracy, let alone during a period of economic constraint and rising public debt.

Harian Kompas (June 2024) recently showed approval at 75.6%,

Indikator (May 2025) had it around 79% approval, 82.7% trust.

Roy Morgan (2024) reported 69% trust in the government overall.

So 90.9%? Sure, it’s possible; but it leans toward the very best-case reading of public opinion. Maybe it’s a genuine surge of early-term optimism. Or maybe it’s a combination of question wording, respondent caution, and the warm afterglow of a high-visibility program rollout.

Whatever it is, we’d be wise to read it with raised eyebrows and a healthy sense of context.

The 2025 ISS offers a snapshot of a country that, at least on paper, feels confident in its direction. The trust in leadership is high, flagship programs like MBG are well received, and satisfaction levels suggest people feel relatively okay.

But scratch the surface and contradictions begin to show. Borrowing rates are high, household spending is low, and trust in political institutions remains lukewarm. This is a case numbers being incomplete rather than them being wrong.

The ISS likely captures a desire to believe that things are improving, or at least that someone is trying. But it’s also true that feeling okay is not the same as being okay.

Surveys like this are valuable, but only if read with care. They tell us what people say, but not always what they live. The trust is valuable. The satisfaction is notable. But when outcomes and emotions drift too far apart, it’s time to start asking better questions.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we help you read between the lines when advising or investing in Indonesia. Contact us to learn what's happening on the ground in workplaces, communities and institutions.