Indonesia’s Human Capital Index: Halfway There, But Going Where?

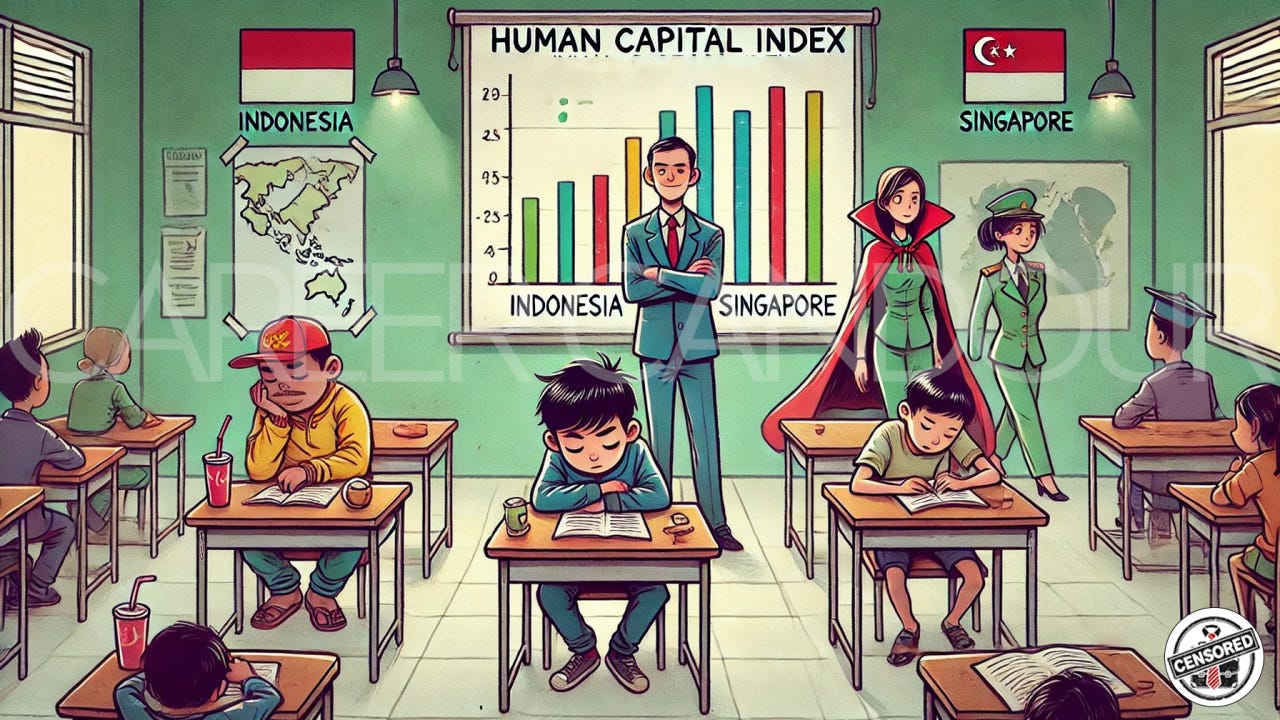

Indonesia scores 0.54 on the Human Capital Index. What does that mean for its future workforce and how does it compare to Southeast Asia?

Imagine being able to distill a child’s entire future potential into a single, decimal-based judgment. Not a hopeful guess or a teacher’s comment scribbled on a report card, but a cold, clean figure stamped into a spreadsheet by economists in crisp suits. That’s the promise of The World Bank's Human Capital Index (HCI); a tool that tries to measure how much human potential a country is unlocking, or more depressingly, squandering.

Indonesia’s score? 0.54 out of 1.0. In plain terms, a child born in Indonesia today is expected to reach just 54 percent of their full productivity potential by age 18, if current health, education, and nutrition trends hold. Not a failing grade, but not one you'd brag about either.

Think of it like this: the child’s future is a car with 100 horsepower under the hood, but the way things stand, they’ll only ever get to use 54 of them. The engine isn’t broken, but the fuel, the maintenance, the roads? They all need work.

And here’s the complication: other countries are upgrading their engines too. So while Indonesia is inching forward, It has to move faster than the very countries it’s hoping to overtake and sustain that momentum for decades.

What the Human Capital Index Actually Measures (And What It Doesn’t)

The name might sound like something out of a sci-fi thriller, but the reality is a bit more grounded. The HCI doesn’t track your salary, your job title, or how many side hustles you’ve got. It isn’t interested in whether you’re managing a tech startup or just managing to get through the day. What it does want to know is this: how much of their full potential is a child likely to achieve, just by growing up in their country today?

It’s built around three simple ideas:

Survival: Does the average child live past the age of five, or does preventable disease or malnutrition cut things short?

Schooling: How many years do kids spend in school, and just as importantly, do they actually learn anything while they’re there?

Health: Do children grow without stunting, and do they enter adulthood healthy enough to contribute productively to society?

The results are crunched into a single score between 0 and 1. A 1.0 would mean a child born today has every chance to grow into a fully healthy, fully skilled adult.

But no country scores a perfect 1.0. Most hover somewhere in the middle, between ambition and structural dysfunction. Crucially, the HCI doesn’t reflect current economic strength or workforce participation. It’s a forward-looking estimate, focused on the raw potential of the next generation. And for countries like Indonesia, that’s where the story starts to feel more like a warning than a compliment. Because while kids may be going to school and surviving childhood, they’re not necessarily being set up to thrive.

Indonesia: The Land of Great Potential and Underwhelming Test Scores

Indonesia’s Human Capital Index score of 0.54 sits awkwardly between aspiration and reality. It’s not rock bottom, but it’s not the kind of number you print on the cover of a development report unless you’re trying to make a point.

Let’s start with what’s working.

The country has made serious strides in public health: 98 percent of children now survive past age five, which would have been an unthinkable figure just a few decades ago.

Education access has expanded too, with children expected to complete 12.4 years of schooling (on paper).

Labor force participation rate is high at 70.6 percent, and the headline numbers suggest a nation on the move.

But then you look beneath the surface, and things get murkier.

The average test score is just 395, well below global benchmarks. When adjusted for learning, those 12.4 years shrink to 7.8 meaningful years. That’s a sign that many students are in classrooms without acquiring the skills they need for the real world.

28 percent of children are stunted, meaning shorter in height, and often in cognitive development too. These effects don’t show up immediately. They surface years later, in the form of limited job prospects and reduced productivity.

Adult survival between ages 15 and 60 sits at 85 percent, lower than neighbors like Vietnam and Malaysia. That’s a gap that speaks to health systems still struggling with non-communicable diseases, access, and quality.

Indonesia is doing many of the right things, but not quite well enough, and not fast enough. The systems are in place, but the outcomes are underwhelming. Potential is abundant. Execution is where the challenge lies.

How Indonesia Stacks Up in Southeast Asia: The Neighbors Aren’t Sleeping

A score of 0.54 on the Human Capital Index may not immediately set off alarms, but it doesn’t earn bragging rights either. Within ASEAN, it places Indonesia somewhere in the middle of the pack. Not at the back, but far from the front.

To put things in perspective, Vietnam scores 0.69; impressive given its lower GDP per capita. Its children average over 500 on international test scores, and stunting rates have declined significantly. Vietnam’s approach has been anything but flashy: focus on basic literacy and numeracy, ensure children show up to school and learn something, and deliver health services that don’t break the national budget. The results are hard to argue with.

Malaysia and Thailand also outperform Indonesia, both scoring 0.61. They benefit from more developed health systems and lower stunting rates. While their test scores aren’t exceptional, they’re high (and consistent) enough to push up their learning-adjusted schooling years above Indonesia’s.

And then there’s Singapore, at 0.88. High test scores, long schooling, universal child survival, negligible stunting. It’s in a category of its own.

Indonesia does have an edge over the Philippines (0.52) and the lower-income Mekong countries. But in a region where everyone is moving forward, standing still is a form of falling behind. The gap is widening where it matters, in learning outcomes and early-life health. These are slow to fix but faster to slip, and Indonesia’s current trajectory suggests that catching up will take urgency. Because the neighbors? They aren’t waiting.

Today’s Workforce: Indonesia Is Working Hard, Just Not Always Formally

Indonesia’s Human Capital Index may focus on the future, but the present workforce tells a story of its own. At first glance, things look encouraging.

Labor force participation rate stands at 70.6 percent, which is solid by regional standards.

Unemployment is relatively low at 4.76 percent, a figure many countries would be happy to claim.

But these top-line numbers don’t tell the full story. Look closer and you’ll find that nearly 60 percent of Indonesian workers are in informal employment. These are not workers opting out of the system for lifestyle reasons. They are not gig economy consultants working from beachside cafés. Most are market vendors, agricultural laborers, domestic workers, or drivers operating with minimal security and few benefits.

Informality limits upward mobility. Without contracts, legal protections, or access to social insurance, workers remain vulnerable to economic shocks. It also constrains productivity. Informal work tends to cluster in low-productivity sectors, with limited technology, training, or capital investment.

This is where the Human Capital Index becomes relevant again. When foundational learning is weak and early health outcomes are uneven, people are less likely to transition into higher-skill, formal jobs. The connection between poor test scores, stunting, and informality plays out in the job market every day.

Compounding this, Indonesia’s mean years of schooling for adults is just 8.77. That’s a legacy of past gaps in access and quality, but it still affects the capabilities of today’s workforce.

So yes, Indonesia is working. But if the goal is to raise productivity, improve incomes, and shift more people into formal, secure employment, then boosting human capital is a present-day necessity.

The Human Capital Index isn’t trying to measure the soul of a nation. It doesn’t account for culture, resilience, or the millions of small, daily efforts that hold societies together. But what it does offer is a mirror. It reflects whether a country is equipping its next generation with the basics: to be healthy, to learn, and to live long enough to use what they’ve learned.

Indonesia’s score of 0.54 is a sign that while some progress has been made, others in the region are moving faster and farther, especially in learning outcomes and early-life health.

Improvement is happening. That’s worth acknowledging. But so is the fact that relative progress matters. In a region where countries like Vietnam are outperforming on less, Indonesia needs to out-improve.

That shift won’t come from just building more schools or clinics. It will come from making those systems better, more consistent, more equitable.

If the goal is to unlock Indonesia’s full potential, the next leap starts in classrooms and health posts.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we help clients build a future-ready organisation, from talent strategy to human capital investments that deliver lasting value. Contact us for workforce solutions that close the performance gap.