Indonesia: Building the Future, One Trade Restriction at a Time

Indonesia has officially earned the coveted spot of most trade-unfriendly nation on Earth. The Tholos Foundation’s 2025 International Trade Barrier Index didn’t mince words: out of 122 countries, Indonesia ranked 122nd. Not “developing economy with constraints.” Not “regional laggard.” Just last. And it doesn’t even come with an asterisk.

What makes this feat even more impressive is Indonesia’s ongoing public commitment to becoming “the next Singapore.” A noble aspiration, if only it weren’t paired with policy decisions that read like the exact opposite of Singapore’s entire economic playbook. Where Singapore opened its doors, Indonesia reinforced its locks.

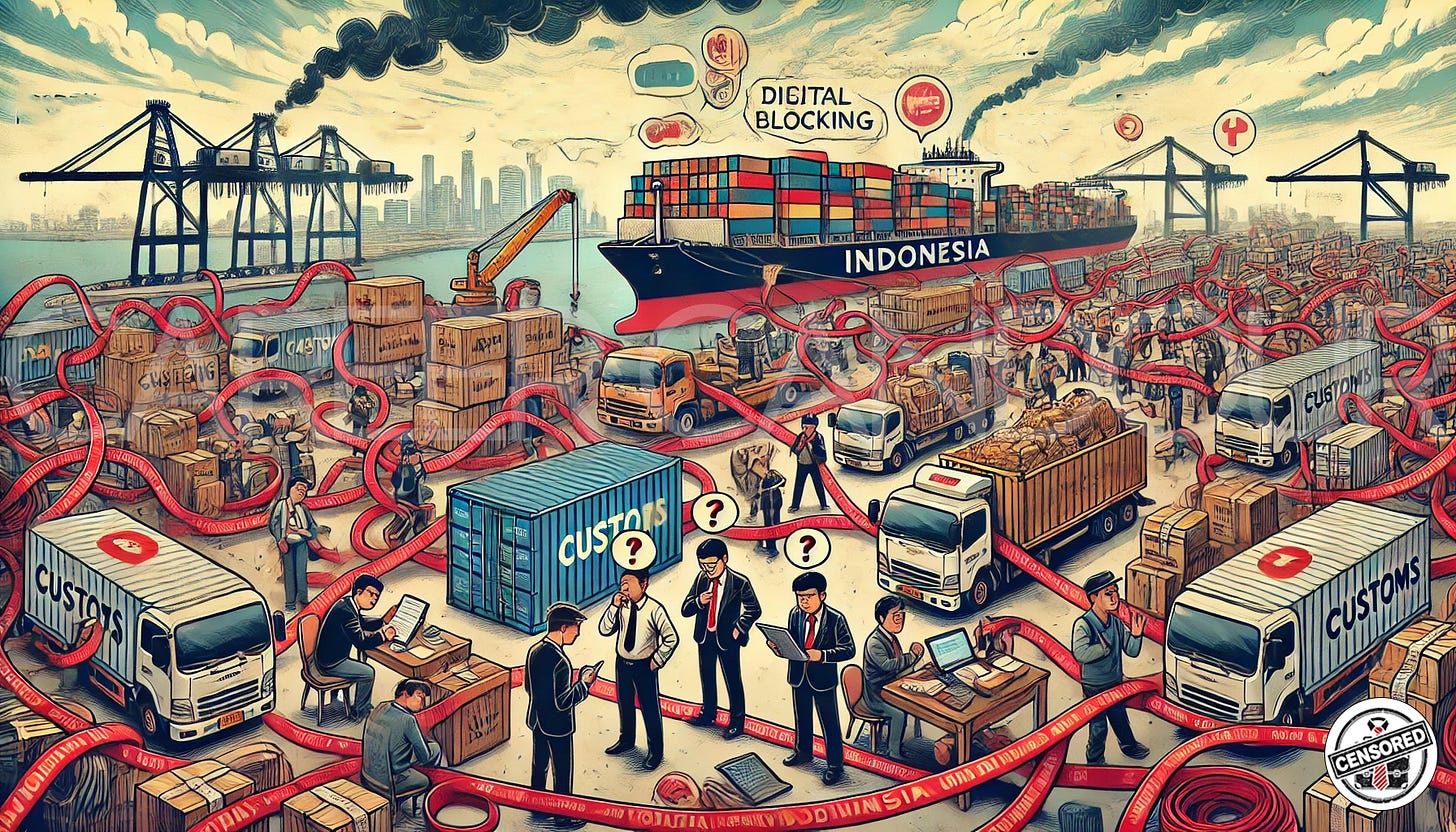

And so, we find ourselves in a nation where imported innovation is discouraged, foreign service providers are boxed out, and digital platforms navigate a maze of fines, filters, and forced local servers. The result? A tangled trade policy environment. Meanwhile, Jakarta’s leaders smile for investment summits, declaring reform, as another foreign brand quietly exits stage left.

How to Win Last Place at Trade: A Masterclass by Indonesia

Imagine shooting a 350 in golf and your coach claps like you've just secured a spot in the Masters. That’s the spirit animating Indonesia’s trade policy: the unshakable confidence of someone doing the complete opposite of what works, then doubling down with a smile. According to the Tholos Foundation’s 2025 International Trade Barrier Index, Indonesia has pulled off the impossible, ranking 122nd out of 122 countries. That’s not “developing with promise.” That’s undisputed champion of economic barricading.

And yet, even as Indonesia crashes through every trade liberalization metric, it continues to posture as an emerging Singapore. Never mind that Singapore abolished tariffs, opened its service sectors, and digitized customs clearance before Y2K. Indonesia prefers the scenic route: 40% import taxes, mandatory local content rules, and smartphone bans that would confuse even the most seasoned supply chain executive.

Foreign investors are met with a mix of awe and bureaucracy. Banks? Restricted. Telcos? Guarded. Engineers? Vetted like spies. Digital companies? Expected to host servers locally, navigate content laws, and preferably not succeed too much.

All this, while speeches at investment forums extol “ease of doing business” and “regional competitiveness” like a mantra no one’s actually tried to live by. It’s impressive. An exercise in how to signal ambition while constructing roadblocks in every direction.

The message? Come to Indonesia… but only if you’re willing to pay, register, localize, comply, negotiate, license, adapt, and not complain.

Singapore: The Path Taken. And Ignored

Let’s pause to appreciate Singapore. It's the poster child for efficient governance, economic openness, and disciplined long-term planning. It’s the go-to role model not just for Indonesia, but for every country from Thailand to Tanzania. And why not? It’s a country that turned a fishing village into a financial powerhouse without needing oil, a military-industrial complex, or prayers to commodity prices.

Singapore is what happens when a government decides to actually implement the reforms it writes white papers about. It dropped tariffs, rolled out free trade agreements, and built world-class ports where containers move faster than political excuses. Foreign banks, tech firms, and services? Welcomed with open arms, provided they followed the rules, which, conveniently, are clear and consistently applied.

Indonesia, meanwhile, points at this model of free-market functionality and says, “Yes, we want that.” Then proceeds to do the policy equivalent of putting sugar in the gas tank.

To be fair, Indonesia is not Singapore, and no one expects it to be. It’s far larger, more diverse, and more decentralized. But that doesn’t excuse the routine decision to avoid reforms in favor of politically easier, economically counterproductive moves, like raising tariffs or imposing localization rules under the guise of “national resilience.”

Instead of copying what made Singapore work: trust in markets, openness to competition, strong institutions, Indonesia has opted for branding over blueprint. “We want to be the next Singapore,” officials declare at summits, shortly before slapping a new import quota on cheese or restricting e-commerce to protect legacy retail.

Protectionism, But Make It Strategic (And Complicated)

It’s not that Indonesia doesn’t want progress, it just wants progress with conditions. Preferably several hundred pages of them. This is growth, Indonesian style: tightly controlled, proudly nationalistic, and layered with regulations.

Exhibit A: Local Content Requirements (LCRs). These are the policy tools designed to "build domestic capacity," which in practice often means forcing foreign companies to make things locally, even when the components don’t exist, the expertise isn’t there, and the infrastructure is lacking. Want to sell smartphones, electric cars, or medical tech in Indonesia? Better hope your circuit boards can be ethically sourced from a small workshop in Surabaya that also sells bottled water.

The outcome is depressingly predictable:

Foreign investors hesitate.

International brands exit, or never enter.

Consumers pay more for products that are often worse.

Even worse, these LCRs don’t just nurture young industries. They actively discourage them from maturing. By sheltering them from competition, they deny firms the very pressure that makes them globally competitive. It’s a policy approach that creates protected industries… and keeps them that way.

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s digital economy is trussed up in data localization mandates, platform taxes, and regulations that require local servers, local partnerships, and local headaches. The message to global tech? Welcome to Indonesia. Now kindly follow 47 separate compliance steps.

This is what “strategic protectionism” looks like: patriotic, procedural, and perplexing.

Why the Expat Bubble Never Quite Pops

Here’s the thing about Indonesia: it’s a country bursting with promise, but also with paperwork. Ask any expat in South Jakarta about Indonesia’s future, and you’ll hear the classics: "massive middle class," "demographic dividend," "the next big thing." All technically true. All consistently stuck in the waiting room of economic inevitability.

The problem isn’t potential. It’s permission. Specifically, the process to get it. Behind the “emerging market darling” narrative is a policy environment that treats foreign involvement like a suspicious house guest. That’s why luxury goods cost double, permits take forever, and highly skilled foreign professionals are often more useful as consultants than participants.

There’s a reason you won’t see expats pouring into Indonesia the way they do in Singapore or even Vietnam. It’s not the heat. It’s the uncertainty, inconsistency, and institutional preference for domestic control. Because for all the talk of being “open for business,” Indonesia’s system is quietly (and very intentionally) designed to favor locals. Not just citizens, but insiders. Family businesses. Connected players. The cousin who somehow runs procurement for three ministries.

And why wouldn’t they? The current system works very well for those at the top. Cheaper imports would eat into cozy monopolies. Easier licensing would invite real competition. And foreign firms winning market share might expose the mediocrity of certain protected champions.

So, yes, foreign direct investment is welcomed, but only if it’s well-behaved, deferential, slow-moving, and preferably joint-ventured with someone whose uncle once ran customs. It’s not anti-foreign; it’s just very pro-cousin.

The expat bubble doesn’t pop because it’s not really inflated. It floats, contained and curated, like so much else here, never quite escaping the comfortable limits of controlled ambition.

The Real Question: Do They Even Want to Change?

Maybe Indonesia doesn’t actually want to be Singapore. Not in substance, anyway. Sure, it says it does, often and enthusiastically, especially when investors are watching or during panel discussions at regional forums. The phrase “next Singapore” rolls off the tongue nicely and looks great in slide decks. But beneath the aspiration lies a reality that tells a very different story. One where the status quo is stubbornly, even strategically, preserved.

This isn’t necessarily a failure. Sovereignty isn’t a flaw. Every country has the right to chart its own path, shaped by its history, institutions, politics, and preferences. But at some point, we have to stop treating Indonesia’s trade posture like it’s just a phase, or a transitional hiccup. Because it’s not. It’s a choice. A deliberate one.

The policies that underpin open economies are not hidden in some secret IMF vault. The playbook is public and proven: lower tariffs, deregulate services, secure contracts, clean up customs, and enter high-standard trade agreements. The fact that Indonesia continues to avoid these steps suggests the issue isn’t lack of knowledge. It’s lack of incentive.

Because true liberalization would upset powerful domestic interests. It would mean ceding some control, exposing protected sectors to real competition, and rethinking who gets to win. And that’s politically expensive, economically disruptive, and reputationally risky, at least in the short term.

So the narrative continues. The ambition to “be like Singapore” lives on, even as policy does the opposite. It’s easier that way. Keep the speech, skip the substance.

Indonesia is not broken. It’s a vital, growing economy, rich in culture, resources, and opportunity. It matters regionally and globally. But it’s also an economy that has made deliberate policy choices, many of which involve building and maintaining barriers to trade. These aren’t accidents or oversights. They’re trade-offs. And they come with costs.

Costs like higher consumer prices, because imports face tariffs and quotas. Less competition, because foreign players are boxed out before they even arrive. Fewer global brands, because compliance isn’t worth the hassle. And limited roles for global professionals, due to opaque regulations and protectionist hiring policies. Add to that a sluggish path toward full integration with global supply chains, and the contradictions start to show.

This isn’t about blaming Indonesia. It’s about recognizing reality, especially for outsiders who assume Jakarta is just Singapore’s laid-back cousin. It isn’t. The two countries play different games with different rules.

So next time someone tosses out the “Indonesia is the next Singapore” line, pause. Ask what they really mean. Then suggest they try importing a Bluetooth speaker. It’s a far more enlightening experience than any white paper. And far more expensive.