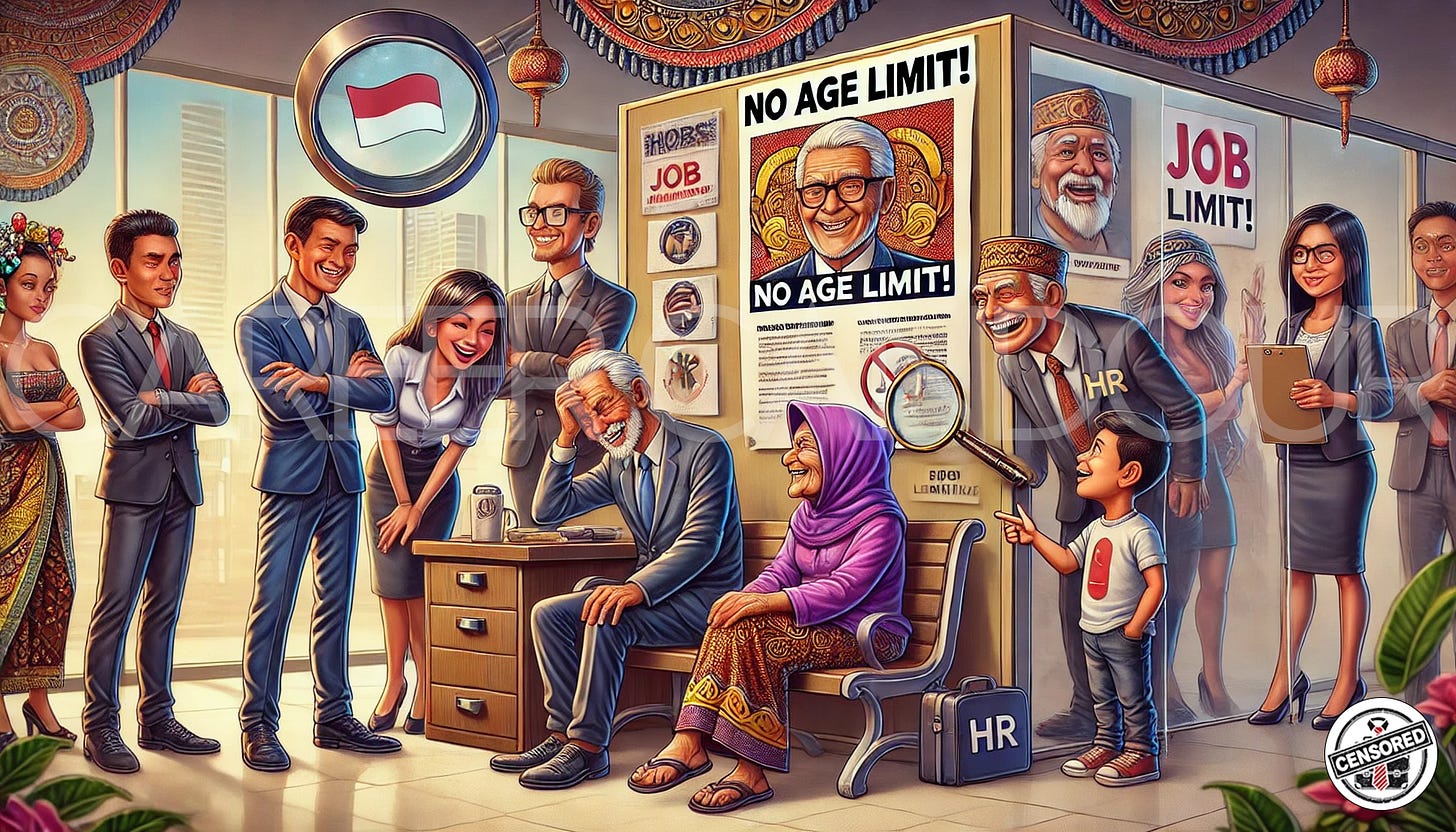

Indonesia Bans Age Discrimination in Job Ads. Problem Solved? Not Quite.

Indonesia now bans age limits in job ads, but without enforcement, hiring bias may continue behind the scenes. Here’s what still needs to change.

It’s official: Indonesian job ads can no longer include age limits. The Ministry of Manpower’s new circular (M/6/HK.04/V/2025) tells employers to refrain from listing age requirements in vacancies, a move aimed at one of the most blatant and longstanding hiring filters. The classic “Max 27 years old” requirement, often attached to roles asking for an S1 degree and multiple internships is no longer allowed.

On paper, it sounds like a leap forward. Job postings in Indonesia have long resembled character profiles rather than role descriptions, complete with preferences for gender, marital status, and aesthetic appeal. Removing age criteria is a good step. But it’s just that. A step.

The deeper question is what happens next. Discrimination rarely needs to be written in ink to function. If age bias remains embedded in hiring culture, then job ads are simply being scrubbed for appearances. Companies can still exclude older applicants quietly, during CV screening or interviews. What this reform risks becoming is a polished front for the same old practices. Job ads might be cleaner now, but unless internal systems change, the discrimination will just move where we can’t see it.

Policy Without Teeth: Circular Letters and the Illusion of Reform

To understand why this policy may not shift the ground beneath Indonesia’s hiring culture, you need to know what a circular letter actually is. In Indonesia’s legal structure, it holds no real legal weight. It’s not binding, not enforceable, and cannot be used as the basis for any sort of legal action. Its slightly more than a polite suggestion but functionally lacks bite, bark, or even a whisper of consequence.

So while the circular’s message that job ads should stop listing age restrictions is commendable, the instrument delivering it is not built to compel change. There is no punishment for ignoring it. A company that continues to post "maximum 30 years old" in job ads won’t be fined, sued, or even publicly named. At best, they might receive a letter. Or a call. Maybe.

This is the central problem. The circular is a symbolic gesture in a system that has long required structural intervention. And symbolism, while useful in starting conversations, cannot substitute for policy with real accountability.

Of course, one could argue that all cultural change starts with symbolism. But in the absence of a legal framework or mechanisms for enforcement, symbolism can become a comfort blanket. It gives the appearance of reform while leaving the machinery of discrimination untouched.

So what happens when the government tells companies, “Don’t do this,” but offers no reason to stop? The answer is predictable. Most won’t. At least not until they have to. And this policy doesn’t make them have to. It simply asks nicely.

Discrimination 2.0: More Subtle, Still Effective

Removing age limits from job ads sounds like a step forward. It is. But it’s also just the first move in a longer game. Because if there’s one thing bias has mastered, it’s adaptation. Once overt language becomes unacceptable, discrimination doesn’t vanish. It shifts. It gets quieter, more coded, and arguably harder to track.

Hiring teams can follow the circular to the letter and still favor youth in practice. No age listed? No problem. Just ask for a “recent graduate.” Or request “1 to 2 years of experience” for a mid-level role that anyone over 30 wouldn’t bother applying for. Or say nothing at all and screen out resumes based on graduation dates or how many job entries someone lists on their CV. The bias still flows. It just avoids leaving fingerprints.

This isn’t a case of rules being broken. It’s a case of rules being circumvented by design. Bias isn’t limited to one line in a job post. It’s embedded in internal processes, in unspoken preferences, in performance evaluations based on how well someone “fits in.”

The terms used may sound neutral. “Team culture.” “Energy.” “Dynamism.” But often, they mask age-based assumptions. That younger workers are more flexible. That older candidates won’t “adapt to change” or will expect too much in salary. These aren’t explicit policies. They’re quiet defaults. And that makes them more durable.

That’s why removing age limits from ads, while meaningful, doesn’t guarantee inclusion. It’s a surface fix that doesn’t interrogate the foundations. If hiring teams aren’t trained to spot their own assumptions, the reform simply creates a more polite version of the same problem. Cleaner language, same outcome. What we need is not just compliance, but transformation in how we think about age and ability.

Before Preaching to the Choir, Maybe Tune Your Own Voice

It’s difficult to take an anti-discrimination policy seriously when the institutions promoting it haven’t applied it to themselves. That’s the uncomfortable contradiction sitting beneath Indonesia’s recent circular on age-inclusive hiring. While private companies are now being asked to abandon age limits in job ads, the public sector continues to uphold many of the same restrictions.

For example, the requirements for Indonesia’s civil service exams (CPNS) often include strict age caps. State-owned enterprises have been known to favor young, unmarried candidates. Certain roles even demand that applicants be of a particular marital status or gender. These are current and routine, written into official documents and normalized across recruitment cycles.

This creates a problem that goes beyond inconsistency. It turns the policy into a suggestion for others, not a commitment by all. If we're serious about eradicating discriminatory hiring practices, the powers that be must lead by example. Otherwise, it risks sending the message that fairness is conditional. That the rules apply, but only when convenient.

Symbolic gestures can start conversations, but real leadership is demonstrated through action. The public sector should revise their own recruitment criteria in accordance with the circular. They have the power to model what inclusive hiring looks like, rather than merely asking others to try it first.

At the moment, the policy comes across as well-meaning but contradictory. Asking the private sector to dismantle a system that the state still participates in weakens its credibility. Reform is far more convincing when the first step is taken at home. And if the government wants this policy to resonate, it should be the loudest voice not just in words, but in practice.

Recruitment Tech, Informal Jobs, and the Hidden Battlefield

A policy can only reach as far as the system it's designed for. In Indonesia, that system includes more than what most formal frameworks account for. While the circular from the Ministry of Manpower addresses job ads and formal recruitment practices, it misses the vast, messy middle where most actual hiring takes place.

More than half of Indonesia’s workforce operates in the informal sector. These are the warungs, kiosks, small workshops, family businesses, and neighborhood salons where job opportunities are rarely advertised in any official way. Roles are filled through WhatsApp groups, neighborly recommendations, or quick chats at the local market. Age preferences are often stated bluntly, without concern for fairness or legality. The circular, polite and well-crafted as it is, never even enters this space.

But even in the formal sector, the digital tools that facilitate recruitment often work against inclusivity. Platforms like Jobstreet Indonesia and Kalibrr may no longer show age filters on the surface, but many of these systems still include backend options that allow employers to quietly narrow down candidates. The outcome is the same: filtered, sorted, and excluded but with fewer public traces.

If the goal is to create fair access to employment, the strategy must extend beyond official job postings. That means working directly with tech platforms to eliminate discriminatory filters at the source. It also means helping small businesses adopt fair hiring tools and creating public campaigns that explain why exclusion by age is a problem, not just an outdated habit.

Without this broader push, the policy may clean up the language but not the practice. It risks becoming a cosmetic reform, tidying up the front of the house while the real work continues, unchanged, in the back.

A Thoughtful Step Forward, But It’s the First, Not the Finish

Let’s give credit where it’s due. The decision to remove age limits from job postings is a step in the right direction. It acknowledges that public messaging matters, that employers shouldn’t be allowed to openly advertise exclusion as a job requirement. It says, clearly, that it is no longer acceptable to tell someone they are too old at 36 or too young at 22. That kind of honesty in policy is rare, and welcome.

But a step forward is not the same as reaching the destination. This policy lacks the muscle to drive real change. Without being written into law, and without systems to train employers, review practices, and hold companies accountable, it becomes a nudge that can be easily ignored.

And the truth is, age is only one part of a much larger, more deeply rooted system of hiring bias. Job seekers in Indonesia regularly face barriers based on gender, religion, family status, skin tone, appearance, and education background. Many of these forms of discrimination are not listed in job ads anymore, but they still shape who gets hired. Some are coded, others are simply unspoken. But they exist.

If we want to fix exclusion in the workplace, we can’t stop at the language. We need to examine the assumptions behind it. That means challenging how recruiters define merit, who they see as a “good fit,” and what kind of workers they instinctively trust.

Changing the words in job ads is a start. Changing the way employers think about who belongs in the workplace is the harder task. But that’s the one that matters.

This circular letter is a start, and starting matters. It signals that age-based discrimination is no longer acceptable, at least not in writing. That’s a small but necessary shift. Language reflects values, and changing the language of job ads is a step toward changing what we accept as normal.

But it is only a gesture. Without concrete policy behind it, without laws that carry consequences and systems that demand accountability, the message risks becoming symbolic rather than substantive. A memo can’t do the work of reform on its own.

Discrimination, in all its forms, is not a surface issue. It is built into assumptions, practices, and habits that have been left unchallenged for decades. It lives in interviews, in shortlisting processes, in casual conversations about “fit.” If we want to address that, we need more than good intentions.

Policies must match the complexity of the problem. They must be supported by education, monitoring, and a genuine commitment to inclusion, not just in public statements, but in daily decisions.

Otherwise, this reform becomes another well-phrased directive that fades quietly into the background. We can aim for more than performative progress. And we should.

Want to align with the Minister of Manpower Circular 2025? At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we offer targeted assessments and practical support to ensure compliance. Book a discovery call.