GDP Per Capita: The Number That Makes Indonesia Look Richer (and the Public Feel Poorer)

Indonesia’s GDP per capita suggests prosperity, but income data, inequality, and informal work reveal a population still far from middle-class security.

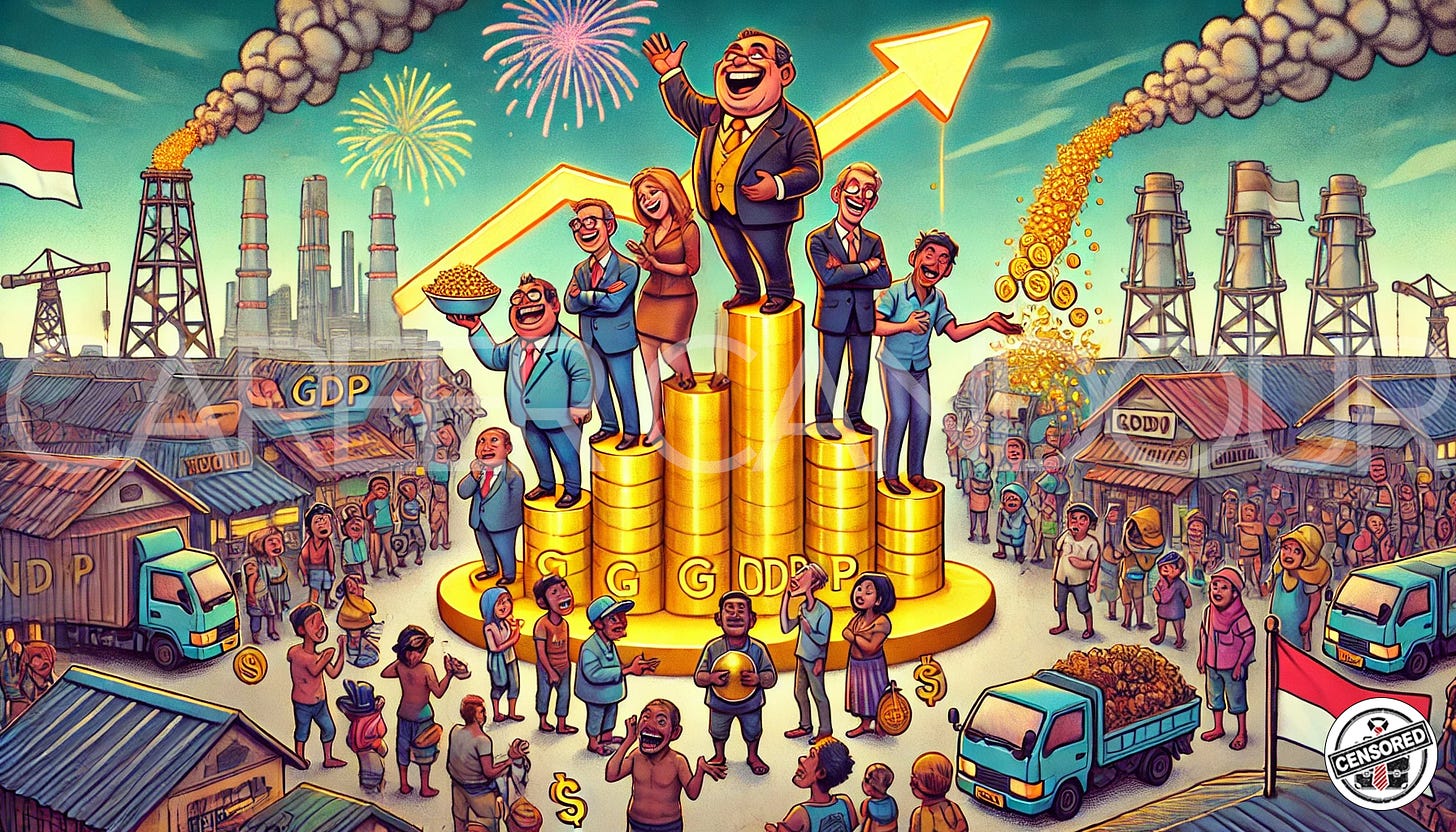

Every few months, international institutions clear their throats. Politicians straighten their ties. A small group of Jakarta-based billionaires nod gravely. Indonesia, we are told, is now an Upper Middle Income Country. They smile as if they personally shook hands with history and negotiated humanity’s graduation to prosperity. And the centrepiece of this celebration? One number so misunderstood, so aggressively misapplied, it may as well be the zodiac sign of the economy: GDP per capita.

You’ve heard the story. “Indonesia’s GDP per capita is rising! It’s nearly USD 5,000! We’re becoming a developed nation!” Cue confetti, cue marching band, cue someone reading a McKinsey report upside down.

Then you look around and notice that while the GDP per capita is rising; your salary is not.

If you ask Indonesians whether they feel 5,000-dollars-per-capita worth of wealthy, roughly two-thirds will reply:

“I would love to meet the person who has my missing $4,000.”

This is because GDP per capita, especially in an economy dominated by natural resources, oligarchic wealth concentration, and large pockets of low-wage, informal work is not a measure of how people live. It is a measure of how value is produced and where it accumulates. It’s a fairy tale. Think Cinderella, except the stepsisters are coal barons and the fairy godmother is the Ministry of Finance.

So while GDP per capita is not lying, exactly. It’s telling a story about output, while skipping the part where most people live.. And that is the story worth examining.

What GDP Per Capita Really Measures

Governments love GDP per capita because it rises even when nothing else does. Investors love it because it compresses a country’s entire economic complexity into a single, tidy number. And LinkedIn economists love it because it requires no follow-up questions.

GDP per capita is deceptively simple:

GDP per capita = Total output ÷ number of people

The problem with GDP per capita is that:

It does not measure income.

It does not measure wages.

It does not measure how money is distributed.

It does not measure who receives it.

It does not measure whether it ever passes through a household at all.

Yet it is often presented as if it were a proxy for living standards, opportunity, or economic health. It’s like measuring the health of a family by averaging everyone’s weight.

Sure, Grandpa weighs 120 kg and the baby weighs 8 kg, but on average we’re perfectly normal!

Indonesia’s GDP per capita in 2024 sat around $4,925, or roughly US$16,448 in PPP terms. That sounds… respectable. It places the country comfortably in middle-income territory.

Then you look at median income, which is essentially the economic equivalent of asking the population, “So how’s life actually going?”

Median income (PPP): roughly US$2,510

GDP per capita (PPP): US$16,448

Meaning the median Indonesian earns about 15 percent of what GDP per capita implies. This is the mathematical footprint of an economy where a large share of value is captured by capital, resource rents, and concentrated ownership rather than by labour.

GDP per capita counts the output of coal mines, nickel smelters, palm oil plantations, financial headquarters, and state-owned enterprises.

It does not ask where the profits go.

It does not ask how many people were needed to generate that output.

It does not ask whether the gains translate into stable jobs, rising wages, or improved household security.

So GDP per capita tells a story of progress, convergence, and upward mobility. While the median income tells a story of slow gains, high vulnerability, and a distribution system that leaks before it reaches most people. Both numbers are technically correct. Only one describes lived economic reality.

GDP Per Capita by Province Tells the Wrong Story

If GDP per capita stretches the truth at the national level, it fully loses the plot at the provincial one.

On paper, the numbers suggest Indonesia is not one economy but a multiverse.

Jakarta posts a GDP per capita of roughly Rp 344 million, or about US$22,000.

East Kalimantan, buoyed by coal and oil, comes in at around Rp 212 million.

Papua Tengah, by contrast, records roughly Rp 120 million.

Read this way, Jakarta looks richer than parts of Southern Europe, while Papua Tengah seems to exist outside modern economics altogether. The temptation is to conclude that Indonesia is split between hyper-prosperous urban centres and regions of extreme deprivation. That conclusion would be wrong.

When you stop looking at production and start looking at people, Median wages across these same provinces do not differ by 30x. They differ by 2–3×.

Jakarta’s median monthly wage sits around Rp 4.6 million.

East Kalimantan’s is roughly Rp 3.5 million.

East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) hovers around Rp 2.7 million.

Look closely.

That’s not “East Kalimantan is 8× richer than NTT,” despite PDRB per capita suggesting that. It’s basically:

“Everyone’s earnings are low, but some people live near resource extraction sites.”

This gap exists because provincial GDP per capita measures where value is booked, not where it lands. Resource-heavy provinces generate enormous output with relatively few workers. Profits flow to corporations, shareholders, and central government, often far from the extraction site.

So is East Kalimantan rich? Yes, in the sense that it produces a great deal of economic value. For the median person, however, “rich province” usually means “your neighbor’s uncle knows someone who drives a company Hilux,” rather than participation in wealth.

Who Actually Benefits from Indonesia’s Growth?

Indonesia’s economic structure could be summarized as:

A few conglomerates, some natural resources, 100 million informal workers, and a dream.

The richest 1% of Indonesians control close to half of national wealth.

The top 10% percent take home around 46% of national income.

The bottom 50% operate on about 12–13% of income.

When output rises, a large share of that increase is mathematically preassigned to a very small group of people.

For everyone else, the numbers look different.

60%+ of Indonesians live under the upper-middle-income poverty line

50–60% of the workforce is informal, earning below the minimum wage.

Median consumption sits around Rp 1.4 to 1.5 million per person per month.

This is the economic reality of the median household. It is stable enough to survive, but far removed from the prosperity implied by headline GDP figures.

GDP per capita happily aggregates everything.

Corporate profits from mining firms.

Resource royalties.

Capital depreciation.

Dividends paid to shareholders who may not live in the country.

Income accruing to politically connected elites.

The value created by commuters who work in Jakarta but live outside it, inflating output without expanding the counted population.

GDP per capita wants to be democratic. It wants to speak for everyone. But by definition it cannot. It is an average in an economy where the average person does not exist.

There is an old saying in Indonesia.

“Rezeki sudah ada yang atur.”

(“Everyone’s fortune has already been allocated.”)

GDP per capita agrees.

Why GDP Per Capita Gets All the Attention

Politicians gravitate to GDP per capita the way a moth gravitates to a flame. Why? Because GDP per capita has several qualities that make it ideal for political storytelling. It is

Simple, which is rare in economics and therefore dangerous in the wrong hands.

Upward-trending often enough to support speeches about progress.

Less embarrassing than Gini, poverty headcounts, or median wages.

Vague about who benefits.

GDP per capita rises, the economy grows, and no one has to specify whose income actually changed.

Better still, it does not ask whether growth was inclusive, sustainable, or evenly shared. It simply announces a number and leaves the audience to clap. Voters, for their part, struggle to relate to it. No one wakes up thinking about per capita output, which makes it difficult to challenge in everyday terms.

Now compare this with the indicators that receive far less airtime.

The Gini coefficient has the bad habit of revealing that inequality remains stubborn, with urban levels above 0.39 and provinces like Yogyakarta pushing 0.43–0.45.

Gross national income is even worse. By subtracting income that flows out of the country, it highlights how much value quietly leaves through profits, dividends, and foreign ownership. This tends to dampen the celebratory mood, so it rarely headlines a press conference.

Median household income directly exposes stagnation. Dangerous.

Poverty at the US$6.85 per day (UMIC line) reveals that over 60% of Indonesians are still “poor” by the standards of countries Indonesia likes to compare itself to.

Household capture ratios show how little growth reaches families. Best to never mention this at all.

These metrics are accurate, specific, and politically inconvenient.

GDP per capita is perfect precisely because it says everything and nothing at the same time. It’s the economic equivalent of saying “I’m doing great!” to your relatives while hiding your bank statement.

Indonesia’s economic narrative works beautifully at a distance.

Yes, Indonesia’s GDP per capita is rising.

Yes, Indonesia is an upper-middle-income economy.

Yes, Jakarta’s GRDP per capita looks like it belongs in the OECD.

But the data makes one thing painfully clear.

Indonesia’s macro story tells you what the economy produces.

It does not tell you what Indonesians receive.

When you consider that:

Median wages move slowly.

Provincial disparities remain vast.

Consumption data shows restraint rather than abundance.

Poverty, when measured against realistic UMIC thresholds, still covers most of the population.

Inequality remains structurally embedded.

Labour informality is the norm.

Large portions of value added flow through natural resource rents and elite concentration of ownership rather than household incomes.

…it becomes obvious that GDP per capita is the least “human” metric imaginable.

Its useful for analysts. Fantastic for ministries. And completely unhelpful if you want to know whether a normal family can pay rent, afford protein, or avoid debt spirals.

Indonesia’s growth is real. But so is the gap between “growth” and “people experiencing growth.”

And that is why GDP per capita will continue to be the star of every policy report and political speech:

It’s flattering,

It’s simple,

It’s easily manipulated,

And best of all?

It says absolutely nothing about how ordinary Indonesians are actually doing.

Its the perfect metric for modern economic storytelling.

At StratEx - Indonesia Business Advisory we advise businesses and investors on Indonesia’s labour market. Contact us to translate economic reality into sustainable talent, pay, and capability decisions.